|

|

|

|||||

|

The settlement at East Heslerton, meaning the Hamlet amongst the Hazel trees, which in the past grew extensively on the north facing slope of the Wolds, is first mentioned in the Domesday Book, completed in AD1086, with the two Heslertons appearing on early maps as Heslerton Magna (West) and Heslerton Parva (East).

The earthworks which are visible in the air-photograph above, taken in the middle of winter so the low light emphasises the relief, mostly relate to the medieval village with the rectangular bank of the manorial enclosure showing clearly . Copyright English Heritage; reproduced with permission. Archaeological evidence indicates that East Heslerton appears to have been established following the abandonment of an earlier Anglo-Saxon settlement situated on open ground about 1.5km to the north-east of this site at about AD875. The situation of the Early Medieval village, in a more sheltered position away from the wetlands covering much of the centre of the Vale of Pickering, may reflect a restructuring of the landscape during the Viking period. Archaeological evidence at West Heslerton shows that the Early Anglo-Saxon Settlement there was abandoned at about the same time in favour of a new village also built in a more sheltered position where the present village survives today. The present village, situated to the north of the church, overlies much of the medieval village. To the south of the church, in land maintained as permanent pasture, much of the manorial enclosure can be seen defined by its enclosing earthen bank. Archaeological geophysical surveys and excavation undertaken to help us understand the development of the village have revealed that it has both shifted its location and shrunk in size since the early medieval period. The earliest settlement activity on the site is indicated by the presence of a small palisaded enclosure built on the rise in the centre of the field; this is thought to date to the Early Iron Age, about 1000-800BC. This enclosure, incorporating a strong timber fence made from tree trunks set in the ground, may have served as a defended refuge rather than as a permanent settlement, with most of the contemporary settlement situated on the sandy lands to the north. Similar but larger examples have been excavated at Devil’s Hill, West Heslerton, just over a kilometre to the south-west and Staple Howe, in Knapton Woods, 3.2km to the west. Adjacent to the palisaded enclosure a ring ditch, roughly ten metres in diameter, may indicate the presence of an earlier prehistoric round barrow or burial mound. Although we have no information about what lies beneath the present village, geophysical surveys to the south show the presence of a number of small rectangular features measuring up to 5m by 3.5m. These are the remains of Early to Middle Saxon Grubenhäuser (from the German meaning ‘hole-in-the-ground-house’, although we no longer consider them to have served as houses). These buildings were created by digging a rectangular hole in the ground over which was laid a suspended floor; this kept the floor dry and made these buildings, which we believe had turf walls, ideal for grain storage. They probably served as general purpose storage buildings rather than houses, but are often associated with larger timber buildings which can rarely be identified through geophysical survey. Grubenhäuser show up particularly well in geophysical surveys based on ground magnetism because they were filled with domestic rubbish and other waste when abandoned and this is magnetically enhanced. It appears as if the focus of the medieval village shifted to the north, probably in the Late Anglo-Saxon period, although it is possible that the village was formerly much larger and the southern part was simply abandoned at this time.

Whilst the surviving earthworks of the later medieval village show up well in the English Heritage air photograph reproduced here, the geophysical surveys show much more detail of the medieval and later village, particularly in the areas beyond the present village to the north and west. To the west of the present village a series of long rectangular enclosures with the short side aligned on the present track coming down from the Wolds are termed crofts and tofts, the toft being where the house was built surrounded by a small garden area, and beyond it the croft, probably used for domestic food production, with the land beyond the village divided up into ‘rig and furrow’, the strip field system that dominated the medieval landscape of much of lowland England. The village was supplied with water from springs at the foot of the Wolds; to the south, the natural stream channel was managed from an early date with the water used to drive a mill and fill the moat associated with the Manor House. The site of the Manor is thought to have been largely destroyed when the present church, commissioned by Sir Tatton Sykes of Sledmere and designed by the celebrated Victorian architect G E Street, was built between 1873 and 1877. Street also designed the vicarage and had further buildings constructed to house the building team. The remains of a number of houses were demolished during the last century in the field immediately to the west of the village and to the south of the A64 trunk road, which cuts through the northern part of the medieval village. The evidence indicates that the village that survives today is considerably smaller than it had been in medieval times and thus is termed a shrunken village.

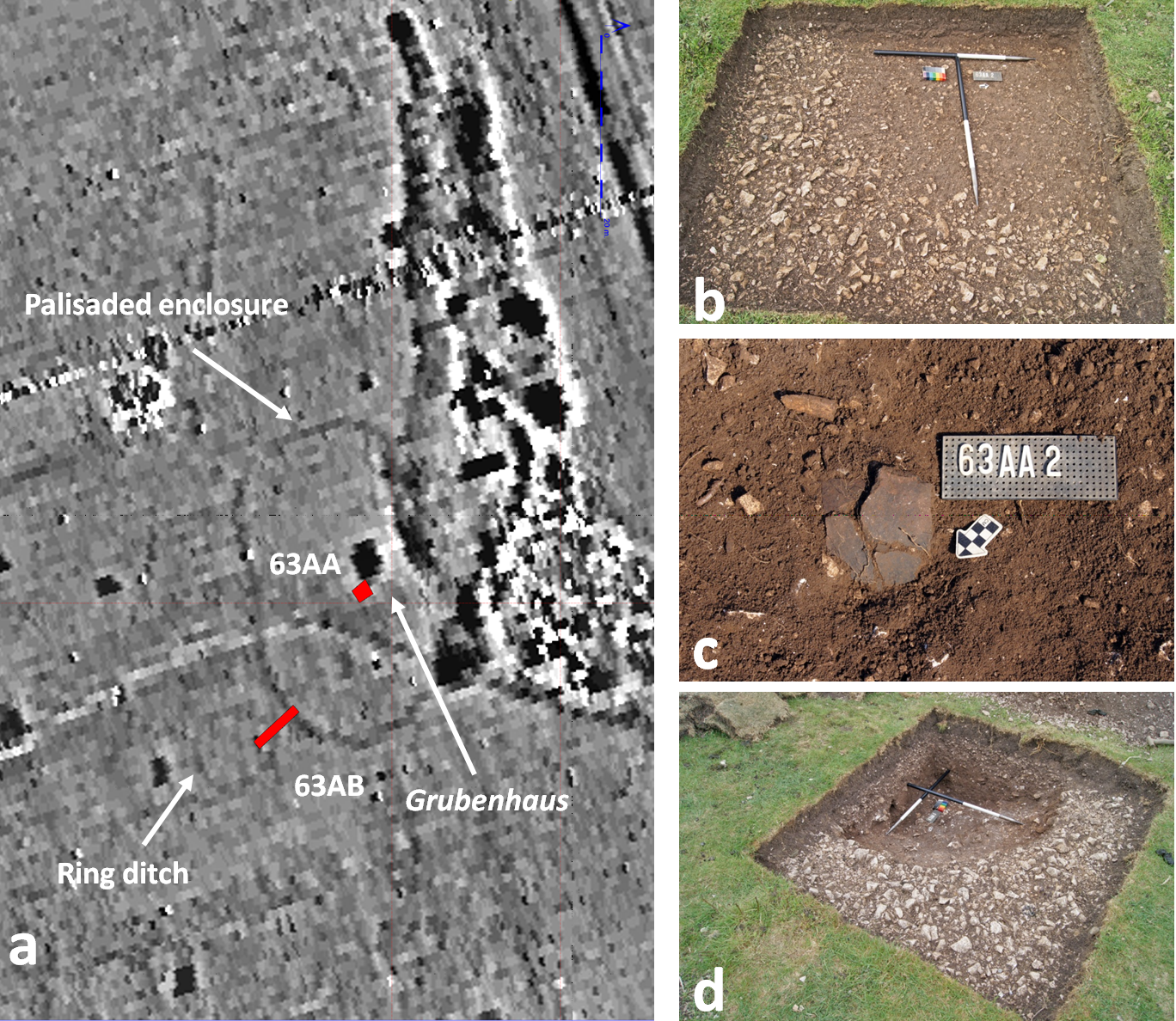

Excavation Results In order to date the palisaded enclosure and test the Grubenhaus within it two very small trenches were excavated. One was situated so as to expose a little under a quarter of the possible Grubenhaus within the enclosure (Trench 63AA), the second cut across the palisade trench and the adjacent ring-ditch (Trench 63AB) as shown in the geophysical survey results (Figure a).

The excavation quickly revealed the south eastern corner of the Grubenhaus which had been cut into the chalk bedrock and was filled with silty soils (Figure b) and domestic rubbish including sherds of Anglo-Saxon pottery and animal bone (Figure c). Once the material filling the pit was removed (Figure d) the rough bedrock exposed in the base confirms that rather than being sunken floored buildings these structures had raised floors, with the pit beneath providing an under-floor air space designed to reduce damp in the building. The silty soils were derived from the walls which had been made of turf and were pushed into the pit when the building went out of use.

The top of the palisade trench was filled with gravelly soil containing a few animal bones (Figure e); below this the lower .65m was filled with lumps of broken chalk (Figure f); amongst these a single sherd of pottery and a few worked flints indicate a date at the end of the Bronze Age and beginning of the Iron Age. The research presented here was undertaken by the Landscape Research Centre with support from The Landfill Communities Fund and English Heritage. We are indebted to Ray Owen of Knapton Quarry, the primary donor, and to Barclays Bank plc, who provided third party funding. We are also grateful to David Lumley who granted permission for the survey and excavation.

|

|||||