|

|

|

|||||

|

Archaeological Investigations on Boltby Scar

The Interim Report on the 2011 Boltby Season is now available as a pdf - click here to dowload The excavations may be complete but the 2011 Boltby Blog combining comments from the splendid team of York University undergraduates and the team from the North York Moors National Park is still available on the web. To download a pdf of the interim report for the 2009 season, together with the Project Design for the 2011 excavations, please click here

Interim Report 2nd October 2009

Boltby Scar during Excavation

Introduction Excavations and associated investigations of Boltby Scar promontory fort were undertaken by the Landscape Research Centre (LRC) during September 2009, on behalf of the North York Moors National Park (NYMNP), as part of the ‘Lime and Ice Project’. The fieldwork was designed to identify and characterise the nature of the surviving evidence relating to the defences of this important site which were sadly levelled by bulldozer in 1961 despite the fact that the monument was a known and scheduled monument. The excavation relied on a small but dedicated team of volunteers, without whom the project could not have been undertaken. We are grateful to all the volunteers for their contribution to the excavation, sense of humour, determination and understanding. In the first week when there was driving rain or later when the constant wind proved very tiring everyone made the journey to site and got on with the tasks in hand with an attitude that made the whole excavation a joy. Although excavations have taken place on Boltby Scar on at least two occasions in the past, virtually no information from these activities survives: a sketch plan and some notes relating to George Willmot’s excavations, undertaken in the 1930’s; a pair of Beaker ear-rings/hair-clips found by Willmot, now held by the British Museum, and various claims as to the antiquity of the site which are unsupported by detailed evidence. The current project is intended to recover new evidence which will allow the condition and nature of the site to be assessed, as well as recover dating and environmental evidence which can form the basis of a detailed interpretation of the site in its context; contributing to resources designed to inform the public about the archaeology of the national park. The current excavation represents the first stage in a project designed both to secure new evidence and identify the potential for reconstruction of aspects of the monument to improve public understanding of this and similar monuments within the national park.

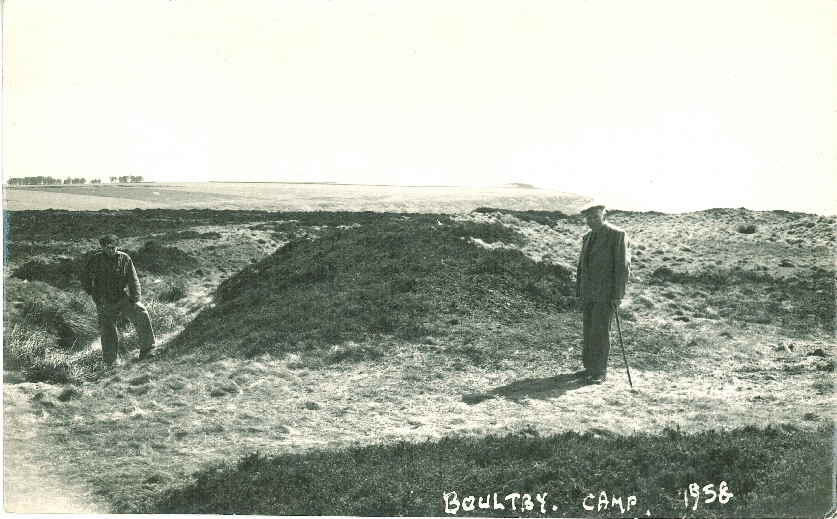

Research approach Although Boltby Scar was bulldozed in 1961 the site remains a scheduled ancient monument protected by the state; the excavation programme undertaken in accordance with agreements between English Heritage (EH), NYMNP and LRC included a combination of auger sampling and trial excavations in three locations within the bulldozed area of the monument. Geophysical surveys undertaken by LRC and a detailed topographic survey undertaken by EH provided the basis for the selection of the three trench locations. A series of auger transects running across the likely location of the former rampart and ditch were designed to gather information on the general scale of the defences and identify any areas where evidence of the rampart might survive. Surviving photographs taken in 1958 show the defences prior to their levelling (Figure 1, Figure 2 ). At first sight these give a false impression of the scale of the monument on account of the fact that they were taken from an elevated position on the top of the bank, but it appears that the bank stood not much more than a metre high at the time.

Figure 1: The entrance to the hillfort photographed in 1958

Figure 2: The defences of Boltby Scar visible in 1958 Three locations were selected for excavation on the basis of the geophysical survey results (Figure 3). The magnetic contrast on Boltby Scar is poor, the most dominant features visible in the survey are the ‘grykes’, polygonal fissures in the underlying bedrock; about two thirds of the filled ditch of the fort shows as a broad curving dark line in Figure 3. The trenches were positioned to examine the entrance (517AA), to examine the ditch and any evidence of a bank where it may have been protected by the eroded base of a round barrow (517AB) and to identify and examine the ditch where it was not visible in the geophysical survey results (517AC).

Figure 3:Boltby Scar Geophysical Survey results overlain with the trench locations

The most northerly of the three trenches was positioned to expose part of the entrance into the monument and the butt-end of the northern ditch segment. Machine stripping of the ploughsoil, a dark and organically rich very stony loamy clay, exposed the ditch terminal as identified in the geophysical survey. The natural subsoil appeared to have been truncated when the site was bulldozed and a small extension was made to check the state of the natural by carefully removing the base of the ploughsoil by hand. The hoped for worn surfaces that we would anticipate finding in the entrance to a hill fort were not encountered and it appeared that the bulldozer had truncated the entrance area by an estimated 25cm. Bulldozer track marks in the natural showed how the bank had been levelled by driving along the line of the bank and others showed the bulldozing in multiple directions across the entrance. The lack of surviving surfaces in the entrance, with the exception of some small areas of iron-pan, which extended beyond the limit of excavation, was somewhat depressing. The nature of the filled ditch was, however, quite the opposite. The 1961 backfill was clearly visible in the top of the ditch where it overlay multiple layers of preserved turf horizons and peat; what had been lost in terms of physical and structural evidence was in part countered by the survival of deposits with a very high potential for the recovery of environmental evidence.

Figure 4: Work in progress removing the lower fill of part of the ditch north of the entrance to the fort

Figure 5: The linear half-section of the ditch north of the entrance prior to backfilling

Figure 6: Excavation in progress at Boltby Scar After the trench was cleaned, washed out and cleaned again, the soils oxidised on exposure revealing what appeared to be the truncated base of the turf beneath the rampart as an area of bleached and leached soil. There was no evidence to indicate stone revetting nor any apparent post-holes that might help interpret the construction of the fort and its entrance; it is quite possible given the limitation in the scale of the trench that any gateway structure lay beyond the limits of the excavated area. Any attempt to extend the trench with the objective of identifying post-holes associated with the entrance would have compromised our ability to complete the work in hand at it was felt that such objectives could be addressed properly at some future time. The leached subsoil can be seen in the foreground in Figure 6 where two partially excavated bulldozer track marks can be seen in the lower right corner of the trench. The excavation of the ditch in this area was concentrated on removal of a single half segment of the ditch to allow us to examine the fills both in cross-section but also through a linear section; in contrast with the section examined in 517AB the primary fill of the ditch contained a considerable quantity of rough rubble. It became clear that whilst the linear section positioned at the surface did not follow the centreline of the ditch the evidence recovered would satisfy our primary research objectives and the rubble layer in the base would be better approached in plan; there was no time for this and the total excavation of this segment should be an objective in future work. It became very clear that the fragile peats that fill the top of the ditch decay very rapidly on exposure. It is also likely that the subtle topographic changes that reveal the position of the ditch on the surface result from desiccation of the buried peat deposits in the ditch fill. Re-examination and further excavation in the entrance ditch sections may help us assess the future survival of the environmentally rich deposits in the face of global warming.

Figure 7:Boltby Scar Trench 517AB after cleaning but washed out by rain As in the case of 517AA, the second trench revealed clear evidence of bulldozer activity with some truncation of the top of the ditch. In addition to the damage inflicted by the bulldozer, subsequent ploughing had left plough marks cut into natural and through the surviving evidence. The positioning of this trench next to a surviving, although robbed, round barrow in the hope of finding better evidence appears to have been a correct decision as part of the former turf rampart had survived despite aggressive ploughing. It seems that some of the spoil generated when the barrow was robbed had sealed the rampart and left the area slightly elevated, reducing the level of bulldozer truncation. As in trench 517AA, the 1961 backfill in the top of the ditch had sealed a magnificent sequence of decayed turf and peat layers providing the potential to document climate change since the ditch first filled in. It became clear very quickly that the ditch on the top of the hill had been substantially filled by the time it was backfilled and the material bulldozed in during the 1960’s was no more than about 25cms thick. Given the very limited scale of the excavations and the level of damage that the site had suffered both from the bulldozer and the plough, the results were very good. Although the ditch was partially truncated in this trench several centimetres of the turf rampart had survived intact despite having modern tracks impressed into the surface. It was clear that the base of the rampart comprised turf laid down, turf-to-turf, on the old ground surface; the area behind the rampart in the interior of the enclosure had been stripped, presumably as a source for rampart material. There was no significant berm between the rampart and the ditch and the back of the rampart had been sealed at the base by a layer of eroded turf material.

Figure 8: Part of the section through the turf rampart showing a probable turf interface and large amounts of rampart fragments in the ploughsoil (Scale 20cms). Having seen the level of damage in area 517AA, the survival of this in-situ fragment of the rampart is remarkable, particularly since the auger transects indicated that this surviving fragment of rampart may only extend for a few metres. As in 517AA, there was no indication that the rampart had incorporated stone revetting, and the very narrow trench was too narrow (with only a one metre segment of the rampart base removed) to provide good evidence as to whether the rampart had incorporated timbering. This question could only be determined through larger trenches than was possible or reasonable within the constraints of this year’s excavation. Whilst the recognition of the base of the rampart was exciting, the ditch section here was both exceptional and remarkable (Figure 9). Very rarely does one see a textbook quality ditch section which gives up its story so we can clearly explain the stratigraphic sequence of filling that is fundamental to all archaeological interpretation. Beneath the 1961 backfill (this included a fragment of natural, bulldozed from the edge of the ditch), the turf survived, and for a few moments was still green before it was affected by the atmosphere; this lay on top of a layer of peat beneath which three further turf lines were visible reflecting a number of drier phases as the ditch had slowly filled. Beneath these organically rich layers, primary and secondary silting run through by a layer of iron-pan indicate that the ditch may have been cleaned out or re-cut on no more than 3 occasions, within a relatively short period. The base of the ditch both in this trench and in 517AC was flat where it reached the surface of bedrock, which, despite the visibility of the grykes in the geophysical survey, was sealed by c.1m of mixed glacially derived clays and gravel.

Figure 9: Excavated ditch section in trench 517AB About a metre beyond the outside edge of the ditch, a small slot (measuring c30cm wide and 20 cm deep and cut at an angle to the line of the ditch) or probable fence trench was clearly visible after initial cleaning. Although of archaeological origin the feature produced no finds and remains undated. It may have held a fence, blocking a gap in the eroded defences to constrain sheep during the last two or three centuries rather than be of prehistoric origin, and it was not visible as a feature in the geophysical survey results. The investigation of the area between the rampart and the barrow revealed very clearly that the turf had been removed from this area as part of the construction process, and although as a consequence the natural was very dirty, no clear features could be identified. The trench extended to the foot of the still extant barrow mound but there was no sign of any encircling ditch; it is possible that a further aggressive clean of the natural may have revealed slight features but this would have left the surviving rampart fragment proud and increased the risk of further damage. A geo-textile layer of Terram was used to line the excavated ditch sections and the important surfaces prior to backfill to protect the evidence in the short term and facilitate the re-exposure of areas if needed in the future.

The third trench was positioned to cross the assumed line of the ditch, which was quickly identified, with further evidence of bulldozer activity where the machine tracks had sunk into the silty clay fill of the ditch and removed much of the 1961 turf evidence as it ploughed through the ditch. In contrast to the two areas opened on the top of the hill the third trench crossed the ditch as it ran down the slope towards the edge of the cliff which bound the site to the west. It was immediately clear that the fills of the ditch here were completely different to those on the top of the hill (Figure 10). The 1960’s turf had been truncated and instead of the turf and peat deposits indicating that the main segment of the ditch had remained wet and often filled with water, for much of the past, the sequence here showed a gradual sequence of silting reflecting the way that this segment effectively formed a drainage gully running to the edge of the hill.

Figure 10: Trench 517AC after unitial cleaning The similarity between the silty clay fills which had washed down and settled in the ditch, and the silty clays of the natural subsoil, made it difficult to identify the edges and sides of the ditch and the organic deposits found in the other trenches were completely absent (Figure 11). The contrast in the levels of organic material in the filled ditch with the other sections is most likely the reason why the other section showed clearly in the geophysical survey. Although the nature of the fills in the ditch here were quite different to those excavated in the other trenches, the central fill did include a number of sadly non-diagnostic sherds of pottery; without distinguishing features the fabric may indicate a Late Bronze or Early Iron Age date.

Figure 11: Half linear section through the southern part of the ditch after removal of the bulk soil samples

Interim Conclusions The defences of the Boltby Scar Promontory Fort were badly damaged and in large areas truncated when they were levelled in 1961. In some areas it seems likely that the surface was truncated by as much as 25cms although - remarkably - adjacent to the surviving upstanding barrow within the monument (another was removed by the bulldozer) a small area of turf rampart and interior surfaces survived. The 1961 backfill alone is of such limited volume that it is clear that that the bank material mixed with natural subsoil was spread extensively over the area. The ditch, where it showed in the geophysical survey, is currently filled with a gradually desiccating sequence of environmentally very rich deposits which may span the period from the Iron Age to the present day. The level of environmental preservation and survival encountered was quite unanticipated. The rate at which the organic fills in the top of the ditch, and initially described in terms of colour and texture with reference to chocolate, decayed on exposure to the atmosphere was astonishing; it made it very easy to explain for the volunteers and the visiting public the role and fragility of environmental archaeological evidence in the context of climate change. In all the trenches the number of finds recovered from the ditch sections is negligible, and does little to confirm the date of the monument, but the survival of so much organic material should enable us to secure accurate radio-carbon dates; we have to await the completion of the environmental assessment before material for dating can be identified and submitted. The lithic assemblage is very small and also dominated by very small fragments of debitage, perhaps largely derived from secondary tool re-working rather than primary manufacture. The ceramics assemblage, including only three substantial sherds is equally limited and although the fabrics are characteristic of a Late Bronze/Early Iron Age date none have distinguishing features that confirm the suggested date. It should be appreciated that the total volume of excavated features was very small (less than the equivalent of a single 2m wide ditch section) given the evidence of surface truncation we would not have expected to find much material beyond that contained in features. There is still much of this story to come from the environmental assessment and C14 dating but the results have been far better than expected. As is always the case new questions regarding the levels of survival in the interior of the fort remain; for instance, was it all bulldozed? Was the rampart timber-laced? Was the gateway in any way fortified? The excavation was a splendid success made possible by a tremendous team including James Lyall and Gigi Signorelli as supervisors, Christine Haughton administrator and finds management, Jen Smith, Graham Lee, Mags Waughman and the many behind the scenes contributors from the NYMNP, Dr Keith Emerick and Dr Alistair Oswald of English Heritage, The Forestry Commission, James Rackham of Environmental Archaeology Services the National Lottery and other contributors to the Lime and Ice Project, including an unexpected large number of site visitors, the children of Gillamoor primary school and lastly but not least the hard working and dedicated volunteers: Sheila Ashby, Judy Bradfield, David Chadwick, John & Siriol Hinchliffe, Chris Johnson, Lucy Knock, Christine & Victoria Lucas, Mark Ridout, Geoffrey Rowson, Elizabeth Sanderson, Vera Silberberg, Geoffrey & Helen Snowdon, Robert Stewart, Catherine Thorn and Stephen Toase. We are also grateful to the landowner Richard Redhead and his family for giving us permission to excavate and facilitating access to the site. We are grateful to everyone for their contribution and hope to meet up again on that windy hill in the future.

Dominic Powlesland Director The Landscape Research Centre October 2009

|

|||||