|

|

|

|||||

|

25 Years of Archaeological Research on the Sands and Gravels of Heslerton by Dominic Powlesland

Introduction On a bleak windswept day early in the spring of 1978 I visited a small sand and gravel quarry between the villages of East and West Heslerton on the southern side of the Vale of Pickering. The broad band of sand and gravel which separates the edge of the wetlands and the foot of the Yorkshire Wolds, often referred to as the sandy lands, is now considered to be of poor agricultural value and might seem an unlikely place for past settlement. In fact, the situation is quite the reverse. Here, a quarry worker, Jim Carter from West Heslerton, had discovered a number of Early Anglo-Saxon burials following the removal of ploughsoil in preparation for the extraction of sand and gravel. Cook and Son's quarry, like many others throughout Britain, was the setting for a chance discovery that was to change our understanding of the past forever. The light sandy soils covering the sand and gravel deposits that span the gently sloping gap between the base of the Yorkshire Wolds and the wetlands that once covered most of the central part of the Vale of Pickering, provided an ideal setting for prehistoric and later settlement.

Cropmarks showing the ditches around prehistoric burial mounds in Rillington

Although we can now reflect upon 25 years of fieldwork, our work is no longer driven by the need to rescue a chance discovery, but by local and national research questions. By combining excavation with other forms of fieldwork we are learning more every day about how people have lived in and changed this remarkable landscape. We hope that through a better understanding we can help develop ways in which parts of this remarkable heritage can be preserved for future generations. It would take over a thousand years to dig all the sites that we have recorded through surveys from the air and on the ground.

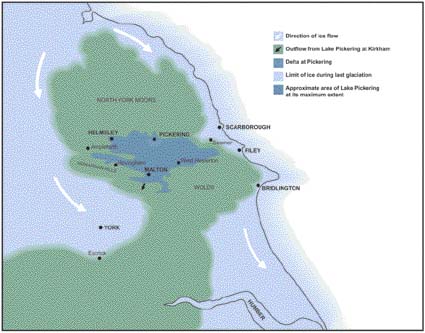

The Vale of Pickering - a most unusual valley. Map showing Lake Pickering at its maximum extent about 14000 years ago The Vale of Pickering is unique in England for here the principal river, the Derwent, flows not towards the coast but inland. It rises just a few kilometres from the sea on the North Yorkshire Moors and runs not east to the sea, but west through the Vale of Pickering and then south to join the River Ouse more than 80km from its source. This unusual drainage pattern of the Vale of Pickering results from changes to an established river valley that originally drained into the North Sea south of Filey. During the last glaciation, which ended about 14,000 years ago, the North Yorkshire Moors appear to have provided a barrier against glaciers pushing south which divided to create a major glacier running down the coast and a second filling the Vale of York. As the glaciers receded, high ridges of glacial till known as lateral moraines were left behind, one blocking off the Derwent's outflow to the sea. With nowhere else to go, the meltwaters of the receding glaciers filled the blocked valley to form Lake Pickering to around the 65 metre contour. Finally the Lake overflowed, cutting a deep gorge between the Howardian Hills and The Yorkshire Wolds at Crambeck. By about 10,000 BC the water level in the valley had stabilised at about 25 metres above sea level leaving Lake Flixton, contained between two moraines at the eastern end of the valley and draining into a very much-reduced Lake Pickering. As the waters drained away, sands and gravels deposited around the edge of the Valley were left exposed whilst, in the centre of the valley, Lake Pickering appears to have been reduced to a large number of smaller lakes that were often separated by long, slightly raised gravel ridges running from east to west. Around these lakes extensive reed marshes and woodland developed, filling the base of the valley. Early Prehistoric Hunters - The Late Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Heslerton is not the only major archaeological site in the Vale of Pickering. The earliest evidence of human occupation in the area comes from the Carr lands at the eastern end of the valley, in particular from Star Carr, where Lake Flixton drained into Lake Pickering, and Seamer Carr, where the site is now buried under the Scarborough municipal rubbish dump. The sites at Star Carr and Seamer Carr, hidden beneath the dark smelly peat that is indicated by the name Carr, have produced worked flint and bone tools, and butchered animal bones dating back as far as 11,000 BC. These flint blades and points were lost or discarded during regular visits to the edges of post-glacial Lakes Flixton and Pickering, which were ideally placed for hunting. By burning the reeds at the edge of the lake new shoots were encouraged to grow, attracting animals to feed at the lake edge where they were easy prey for the skilled hunters of the Late Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age. As the climate warmed and became wetter, extensive reed beds formed around the lake edges and over thousands of years a thick layer of peat formed. Peat, which comprises partially decomposed plant material, develops in stagnant waterlogged areas where there is insufficient oxygen in the water to support the microbes which would otherwise consume the plant remains. Peat is an important resource that acts as a natural sponge holding as much 90% of its volume of water. In the past, the extensive areas of peat in the valley bottom would have moderated the risk of flooding in the Vale of Pickering, expanding to hold more water during very wet times and then gradually shrinking as the water drained away during periods of drought. Peat is of great importance to the archaeologist because within it pollen, insect remains and other organic materials can survive for thousands of years. Pollen found in peat deposits is the best source of information for the reconstruction of ancient environments which, in turn, can help us understand past climates. Excavations following the edge of Lake Flixton, carried out by the Vale of Pickering Research Trust over more than 20 years, have shown that the water level in Lake Flixton remained static for over 5000 years spanning the period from the end of the Palaeolithic into the Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age. During this period the lake edge provided an important and constantly re-visited hunting ground. We can be certain that the situation was similar elsewhere in the valley, associated with the many lakes and pools which were the surviving remnants of Lake Pickering. Until less than 200 years ago there were widespread peat deposits over much of the Vale of Pickering. As the boggy Carr lands have been drained the peat has decayed away, the ground level has sunk and, with the introduction of intensive arable agriculture into these areas, most of the early prehistoric sites have been badly damaged or lost altogether to the plough. The earliest evidence of human activity so far discovered in the excavations in and around Heslerton dates to the Late Mesolithic at about 5000 BC, when tiny `microlithic' flint blades were used to make complex composite tools. Rather than make a spearhead using a single large flint blade, multiple small blades were set into bone, antler or wooden hafts using tree resin as an adhesive. Although we have found only a few microliths, their discovery alongside an ancient stream channel emerging from the foot of the Wolds may indicate that this area was also used for hunting and probably also as a routeway linking the centre of the Vale to the lower slopes of the Wolds. It is difficult to get a clear picture of the Vale and its people during early prehistory. Fragments of worked flint show that the Vale supported a small population at least, living as hunter gatherers on a mixed diet of fish, fowl, meat and fruit and nuts, using their flint tools to work wood and leather, and producing woven materials such as baskets and matting. Although there is a tendency to think of the landscape at this time as being covered by dense primeval forest, it is likely that extensive areas may already have been cleared, sometimes by fire following lightning strikes, and at others deliberately cleared using slash and burn techniques, leaving open areas and areas of scrubby re-growth particularly on the sandy lands where tree cover would take a long time to regenerate. The Mesolithic population were little different to people today and knew that forest clearings made perfect locations for trapping and killing animals for food. Although the discovery of flint tools shows that the area supported a population during the early prehistoric periods, the people who made these objects were nomadic and their settlement sites are difficult to identify. We do not really know what they may have looked like; it is most likely that they used tents which were progressively moved from one camp site to another as the year progressed. It is likely that camp sites may have existed on the slightly elevated sand hills around the lakes; Star Carr for instance was once interpreted as a permanent settlement site although this view is no longer accepted. At sites like Star Carr they hunted elk, red deer and horse in addition to wild fowl and presumably fish. During the Mesolithic period the land-bridge which linked the British Isles to the European mainland was breached as the climate became warmer and sea level rose; it is likely that many important Mesolithic sites lie beneath the North Sea. A detailed study of the sands and silts in the ancient steam channel examined during excavations at Cook's Quarry in Heslerton indicate that the blown sands, which become an important feature of the archaeology of the Heslerton area, were already starting to form by the end of the Mesolithic, showing that some open areas must have existed. The Agricultural Revolution - The Neolithic

In Heslerton a huge long barrow was constructed on the top of the Wolds during the first half of the Neolithic. This monument, which was partially excavated during the 1960s, was over 120m long and would originally have stood over three metres high. The mound, made of chalk quarried from ditches on either side of the monument using pickaxes made from antlers, must have been a most imposing structure. At its eastern end the barrow was fronted by a curved setting of huge tree-trunk posts. Although this structure was built on the top of the Wolds, it was set back from the edge and would only have been visible from limited parts of the landscape. Although part of the eastern end of the barrow had been quarried away, probably in the 19th century, and most of the eastern half was subsequently almost completely levelled by ploughing, the western half of the barrow still survives to a height of over a metre. During the excavations at Heslerton a number of important Neolithic features have been examined. These fall into three groups: structures associated with burial, landscape monuments including three hengiform monuments, and a large number of `avenues' comprising posts and pits that often contain burnt hazelnut shells, animal bone and pottery which may be associated with domestic activity. The pits themselves may have originally been dug as storage pits for hazelnuts which were a valuable food source. The first evidence of what we can now show to be widespread Neolithic activity was discovered at Cook's Quarry, the first site we were to excavate. The light sandy soils which sit atop the sand and gravel deposits must have provided an ideal setting for early agriculture, in which the first cereal crops of einkorn and emmer wheat were probably planted individually using simple digging sticks in much the same way as a modern gardener uses a dibber. These soils, whilst easy to work, would have rapidly become less fertile, and it is likely that during much of the Neolithic relatively small areas were under cultivation. The absence of fertiliser and what would then have been relatively thin topsoils would have supported a few years growth before productivity dropped and new areas were cleared; as far as we know there were no formalised fields during this period. The excavations at Cooks Quarry produced evidence of tree felling or wood working in the form of fragments of polished axe which may have broken off during use. The first of a number of hazelnut storage pits were also found here. These features, which seem to be associated with relatively Late Neolithic activity, often include finely decorated pottery which is classified according to the style of decoration employed. A remarkable discovery, the importance of which has only recently become clear as a result of a We have examined three henge monuments - two large examples measuring more than 50 metres in diameter with entrances to the east and west and a third, much smaller example, about 28 metres in diameter with a single entrance to the north. The largest of the three, located in East Heslerton and measuring over 65m in diameter, was first identified through air photography and then mapped in more detail following a geophysical survey. Its situation, partially enclosing a low chalk knoll overlooking the valley, is almost identical to one fully excavated in the mid-1980s at West Heslerton. These monuments, the function of which remains unclear, appear to mark the first indication of human reworking of the landscape; there is no indication that they served either defensive or settlement purposes. In the case of the larger henges, they were built on the very edge of the light sandy soils, in slightly elevated positions where they would be seen from afar. The smaller monument excavated at Cook's Quarry in 2002 appears to be aligned on a short avenue of massive posts extending northwards towards the edge of the wetland that still filled the bottom of the valley. The term henge, when applied to this small monument, is perhaps too grand; we have yet to confirm its date using radiocarbon dating and it may ultimately turn out to be a new class of burial monument. There were virtually no finds associated with this feature, but near the centre two massive pits had contained posts more than 50cm in diameter; next to one a cremation had been buried in some sort of bag. As the posts decayed, large amounts of cremated bone fell into the voids left by the rotting posts. One is tempted to wonder if these pits had contained inverted tree trunks like those found in 1999 at Sea Henge in Norfolk, on top of which the cremations had originally been placed. An alternative mode of burial, excarnation, where the body is left exposed to the elements until only the bones are left, is hinted at in nearby Barrow 1R, where fragments of disarticulated bone were scattered around what appears to have been a timber mortuary house. Unfortunately only half of this monument was excavated in 1982 and by 2002, when the remaining half was examined, some 5m of the monument had been removed by quarrying and we were therefore only able to excavate the front and back of the mortuary house.

To the left is a geophysical survey of a henge monument in East Heslerton, over 65m in diameter. Above is the Site 2 Henge at West Heslerton during excavation

The construction of these mysterious monuments may represent the first demonstration of people's increasing control over the landscape. As with so much in archaeology, we are tempted to see these as `ritual' monuments; whatever the case, it appears that the henges and the great post-pits are related and that they form part of a constructed landscape, a giant architectural adventure incorporating large monuments of earth, stone and timber. They, and the large number of round barrows that were constructed during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, dominate the areas of light soils that provided the setting for early agriculture. It is likely that they were maintained, possibly by grazing with sheep and goats, since they are re-visited and re-used for thousands of years. During the late Neolithic we have the first evidence of settlement. Associated with, but some fifty metres away from the henge in West The First Industrial Revolution: The Bronze and Iron Ages We have seen how in the Neolithic the landscape was fundamentally changed by the intervention of people, people whose lives were concerned primarily with taking control of the landscape and managing food production. Early farming, when combined with hunting and gathering, must have produced sufficient surplus to leave time for major construction works and for development of new technologies like polished stone tools and pottery. There is no indication of great population pressure and, although polished axes and mace heads may be seen as weapons, they are more likely to have been symbols of power. Societies throughout Britain were connected by trade networks, bringing polished axes to Eastern Yorkshire from as far away as Cumbria and Cornwall; by today's standards these items must have been immensely valuable. Not until the end of the Neolithic do we see the construction of the first monuments that might be interpreted as defensive. One is tempted to see the landscape as being made up of a large number of linked tribal lands held and maintained through a type of shared ownership, a populated landscape but with room to spare. During the Bronze Age this all changes, and we see wealth and power articulated through weapons, the dividing up of the landscape into large `estates', and the construction of defensive sites, either as a demonstration of power or out of a need for one community to defend itself from others. The Early Bronze Age is in many ways indistinguishable from the Late Neolithic. An increasing range of pottery styles, some with continental European influences, may have arrived here as a consequence of migration. Whether it was the people who moved, or simply the Beaker pottery tradition, this `new age' was heralded by the introduction of metalworking, first copper, rapidly followed by bronze (nowadays frequently referred to as copper alloy).

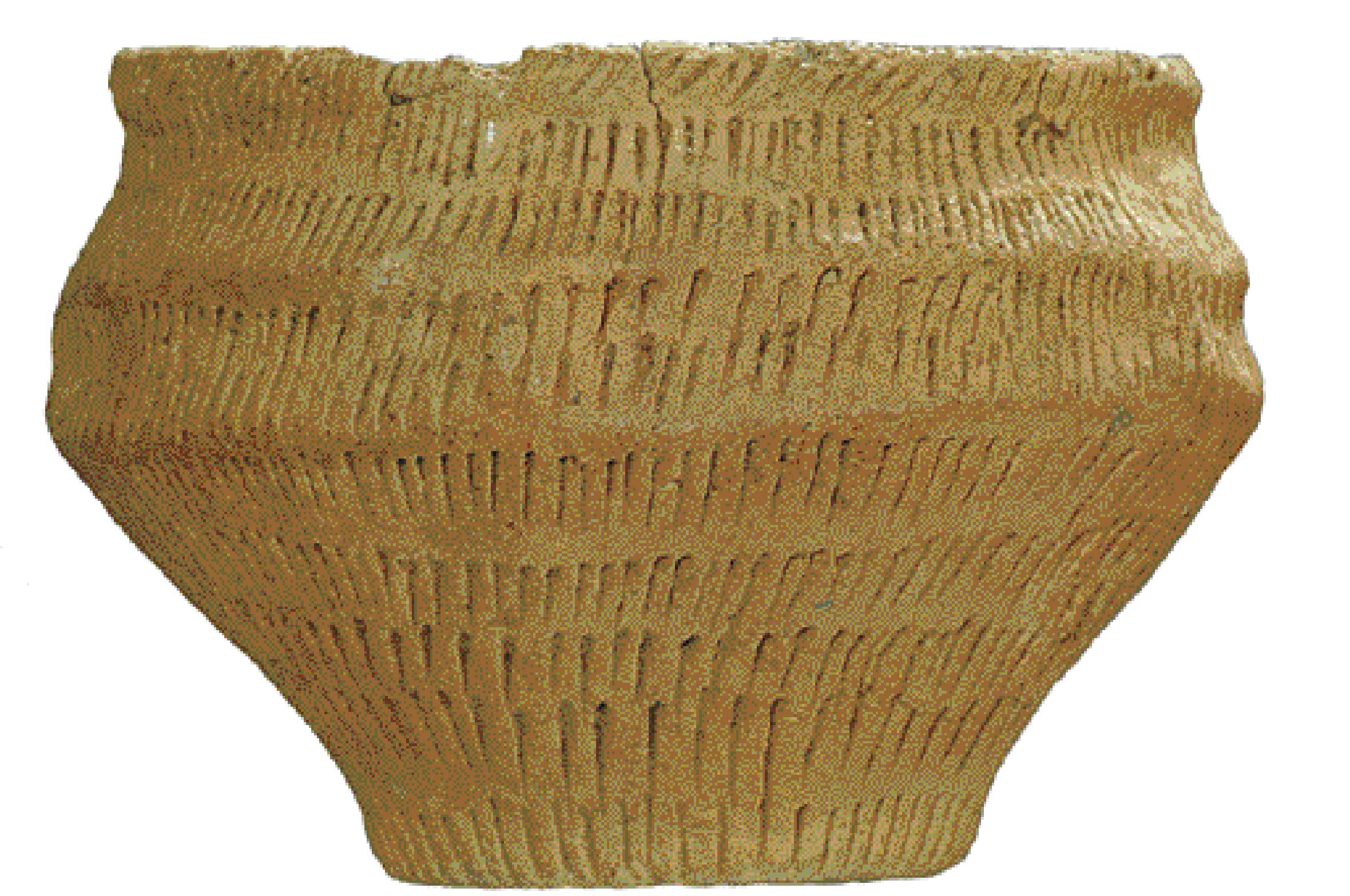

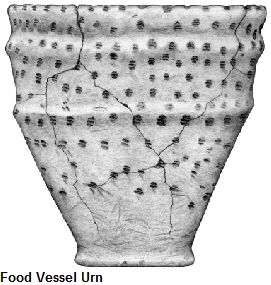

Early Bronze Age Beaker and Food Vessel By the end of the Neolithic period burial in what appear to be family monuments becomes widespread; round barrows up to 30m in diameter are constructed in cemeteries which are often clustered around the large earlier monuments. This tradition continued into the Early Bronze Age leaving a large number of barrows which, in areas where they were built mostly of stone such as the chalk Wolds or Downs, survived relatively intact until the introduction of mechanised farming. These barrows in particular were to catch the attention of some of the great early archaeologists such as JR Mortimer or Canon Greenwell, who excavated hundreds on the Wolds and the Moors at the end of the 19th century. There has been a tendency to see these barrows as the burial mounds of tribal leaders, made obvious by covering the burial with a great mound of earth or stone; the excavations at Cook's Quarry and on the Dawnay Estate tell a different but more interesting story. In the period between about 2200 BC and 1600 BC, when Beaker pottery styles are found all over Britain, often occurring alongside more localised pottery traditions such as the Food Vessels found in Yorkshire and Scotland, two distinctive barrow building styles can be seen in Heslerton. Large barrows of about 30m in diameter are found in cemeteries located in the centre of the sandy lands, whereas smaller barrows feature around the large henges on the southern margins of the sandy areas. The large barrows, of which we have excavated three (1M, 1L and 1R), were all buried beneath blown sands which, in the case of Barrow 1L, had hidden the monument from view since the Roman period at the latest. It is exceptionally rare in Britain to find prehistoric monuments which have been protected from the effects of agriculture or the

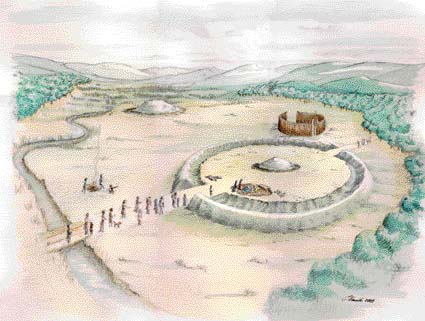

Barrow 1L with most of the mound removed and visible in the baulks. A number of graves can be seen as dark patches in the sand. Food Vessel burial during excavation on Site 2 attentions of early archaeologists and antiquarians. Because these sites were hidden from view, their final discovery the result of a chance discovery by a quarry worker, the details of their form and construction are well preserved. In all three cases it is clear that the barrow mounds were a very late feature; each had started life as a small flat cemetery surrounded by a shallow marker ditch or gully. Multiple burials were made within the enclosed area, and included both cremations and inhumations. When there was only limited space for further burials, a much deeper enclosing ditch was cut and an earth mound thrown up over the graves; a small number of later burials were then either cut into the mound or, as in the case of 1L, cut into the partially filled in ditch. In 1L a grave was cut into the mound within only a few weeks or months of the mound being constructed; we could see where the spoil removed whilst digging the grave had been thrown across the open ditch and the area then cleaned up when the grave was filled in. In the case of barrow 1R, where the barrow was established around the Neolithic mortuary house and over one of the great totem pole post pits, radiocarbon dates show that one grave had been disturbed some 800 years after it was first cut, the body being carefully stacked to one side to make way for a Beaker burial. The western side of barrow 1R, excavated in 2002, was not defined by a ditch but by a meandering stream channel. The constant wetting and drying of the sands into which the burials had been cut had created an environment in which not a single scrap of bone survived and, despite very careful excavation, nothing was found in eleven features which, given their size, shape and location in the barrow, must have been graves. The smaller barrows, including two examples found within the large henge excavated at West Heslerton, measured 10-12m in diameter and contained inhumation burials that had been placed in tree trunk coffins, where a large oak tree had been split in half and hollowed out. Most were accompanied by pottery vessels, particularly Food Vessels. Each barrow contained only three or four grave pits, in two of which later cremation burials had been inserted into the top of the main grave pit. Not all burials at this time were covered by barrow mounds, nor were those buried beneath barrows necessarily better furnished. A fine Beaker burial accompanied by a jet button was found in what appears to have been a flat grave a few metres from the two barrow mounds within the henge, whilst just outside it a cremation of a young child was found beneath an inverted Food Vessel Urn. Although we have plentiful evidence of burial during the Early Bronze age the evidence for settlement is very limited. The inclusion of grave goods with many of the burials indicates a belief in the afterlife, the dead being buried fully clothed and accompanied by short and wide mouthed Food Vessels, which probably did contain food, or tall and slender Beakers which are thought to have contained liquid. Examination of pollen grains found in Beakers in Scotland indicates that they may have contained an alcoholic beverage like mead. By examining the skeletons we can show that these people were relatively healthy and of similar stature to people today and that in some cases they survived into old age. The picture of domestic life is much more difficult to assess; bog-oaks, preserved in the peat in the eastern end of the valley, together with the pollen record, show that the climate became warmer and wetter. Much of the North York Moors would have been good agricultural land at this time; the rise in temperature and rainfall accelerated peat formation. The countryside teemed with wildlife and the lakes and pools in the centre of the valley would have been a good source of fish and wildfowl. Small circular arrangements of small post or stake holes identified during excavation at Heslerton may be the remains of Beaker period houses, but they lack the domestic refuse that would confirm this interpretation. Artists impression of the LateNeolithic-Early Bronze Age monument complex at Heslerton at around 1800BC. It is not until the Middle Bronze Age, between 1600 BC and 1100 BC, that we see the first clearly recognisable domestic structures in the excavations at Heslerton. Also at about this time there seems to be a change in burial arrangements; new cemeteries are established on long narrow ridges towards the middle of the Vale of Pickering. These cemeteries continue to be utilised until they reach their maximum extent during the middle of the Iron Age at about 500 BC. Like the possible round houses identified from the Early Bronze Age, the Middle Bronze Age structures are circular, measuring about 10m in diameter with walls supported on small stakes. These were difficult to see as they had been set in very small stake holes in an area of chalk gravel. These buildings do however have distinctive porches, constructed with much larger posts some 2m to the east of the wall line. Three of these structures have so far been identified and it is likely that the walls were made of wattle and daub and that the thatched roof extended to cover the porch post-holes. A small group of cremations over 200m to the west of these structures may be contemporary. Two of them were contained within pottery vessels, but all were in shallow pits that had subsequently been badly truncated by ploughing. The Bronze Age is best known for the metalwork after which it is named, yet we have so far found only two tiny copper awls. We have been shown a number of examples of metalwork found elsewhere in the Valley, including a bronze socketed axe that was being used to open paint tins in a farm workshop. In contrast to stone tools, which could only be re-sharpened a few times before being discarded, bronze is recyclable. Utilising tin from Cornwall, copper from Ireland and lead probably from the Peak district, this material was too valuable to discard; when a bronze tool broke it would be kept until it could be melted down and re-made, probably by a travelling smith. Bronze Age metalwork is most commonly found in hoards, deliberate deposits made for religious purposes; a probable example is a Bronze Age sword found in the Costa Beck, near Pickering. Some pieces are occasionally found during farming and others sadly come to light when found by treasure hunters who destroy the setting which, if excavated properly, could give us valuable information about the deposit and the people who made these items. Towards the end of the Bronze Age another major transition occurs in the landscape. At this time we have the first clear and detailed evidence of settlement, both on the sandy lands and on chalk knolls overlooking the Vale of Pickering on the north- facing slope of the Wolds. This is a period for which we have no excavated burial evidence. During the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, between about 1100 BC and 800 BC, new societies emerge which appear on the basis of domestic items, weaponry and dress fittings, to have had strong links with communities elsewhere in northern Europe, particularly northern France; they are often referred to as La Tène cultures. The constant influx of European influences throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages, whether through migration or trade, reflect a sophisticated and connected society in which barriers of distance and language were evidently overcome.

By the middle of the Iron Age a new culture had emerged, once again with links to northern France. The Arras culture, best known for its square-ditched barrow cemeteries and, in particular, the so-called chariot burials. Square barrows, defined by a shallow square ditch and containing a single inhumation in a coffin, are most common in Britain in Eastern Yorkshire. A huge square barrow cemetery has been recorded using air photography on one of the gravel spurs in the wetland area; unfortunately the ground conditions in this area have prevented the survival of human bone and all that remains are the stains left by the plank coffins that contained the burials. We have yet to excavate any settlement evidence associated with these cemeteries, but we believe they are associated with a new trackway that is established following the edge of the wetlands on the northern edge of the sandy lands. This trackway was the prehistoric equivalent of the current A64 and ran for many kilometres along the edge of the wetland; it continued to act as the main focus of settlement for about 1000 years, through the end of the Iron Age and the whole of the Roman period.

Excavation of an Iron Age ‘chariot’ burial by the British Museum at Wetwang By the end of the Iron Age it appears that a new form of burial monument replaces the square barrow and, from their distribution and number. We can see that there is a large farmstead with its own cemetery situated at roughly 250 metre intervals all along the trackway. These burial features are like tiny barrows, each containing a cremation within an area defined by a steep-sided ditch or slot measuring as little as two metres in diameter. It is possible that the slot contained timbering that retained a shallow mound, no more than a metre high, made up of the material derived from the slot. We excavated parts of ten examples in Sherburn in 2001; they had been severely plough-damaged and we have yet to confirm their date using some of the tiny fragments of cremated bone and teeth recovered from the surrounding slots; they were however associated with Late Iron Age pottery. During the Iron Age we see the establishment of the first extensive field systems, defined by relatively slight ditched boundaries. Sheep and goats become an increasingly important part of the economy, producing both milk and wool. From the Iron Age until the medieval period wool production for textile manufacture in eastern Yorkshire was to be a cornerstone of the agricultural economy. Loomweights and bone weaving combs are common finds on Iron Age settlements. By the time that the Roman legions established the fort in Malton, the Vale of Pickering was well populated with ribbon development along major trackways following the edge of the wetlands on both sides of the valley. Whilst the centre of the valley remained wetland, and there were large tracts of open downland on the Wolds, the sandy lands supported a large population and extensive field systems. The trackways linking the Vale with areas beyond formed the basis of widespread trade networks. Tribal societies covering large areas of countryside were fully established and were perhaps administrated from high status sites like the hill fort that is lying hidden beneath Scarborough Castle. A massive series of banks and ditches cutting off the spur that connects the North Yorkshire Moors to Scarborough above Snainton, on the opposite side of the valley to East Heslerton, may form the first line of defence for Scarborough; the multiple banks and ditches would not only have stopped chariots, but would also have made cattle rustling extremely difficult. The Impact of Empire: The Roman Period There is reason to believe that the tribal leadership in Eastern Yorkshire struck some sort of deal or at least established a special relationship with the Roman invaders. As far as we can see from the archaeological record, the impact of Rome on the population of the Vale was minimal. The rural economy, the settlements and the trackways continued in use as before, the most significant change being the introduction of mass-produced pottery and other domestic goods, and the coinage with which to purchase it. Evidence from soil analysis shows that during the Roman period the lower slopes of the Wolds, which are on heavier soils, were probably ploughed for the first time, while woodland was cleared on the higher slopes. Perhaps it was necessary to open up new areas using improved Roman ploughing technology to generate the extra produce required to pay Roman taxes or to supply the Roman garrison and town at Malton. The sophisticated stone buildings of this period at Malton, and the few known villas, were the exception rather than the rule; most of the rural population lived in round-houses with wattle and daub walls and thatched roofs. Apart from textile production, other industries developed as a result of increased specialisation. Pottery kilns were established at Knapton late in the Roman period, and its products traded widely throughout the region. The relatively crude Knapton storage and cooking vessels were outshone by higher quality table wares produced in Norton and at Crambeck. The results of our geophysical surveys between Sherburn and Heslerton show that the trackway that linked the many Iron Age farmsteads became built-up for much of its length, with networks of overlapping enclosures forming stock and settlement enclosures linked to adjacent fields. Linear settlements of this type, termed ladder settlements on account of their appearance in crop marks, are found along the Great Wold valley as well as in the Vale. Although you may read that the Roman period ends in AD 410, the archaeological evidence from the Vale of Pickering and many other sites in Britain indicates that by the middle of the 4th century AD many of the towns and the Roman economy in Britain were in a state of collapse. The romantic picture so often painted of life in Roman Britain ending in a sudden collapse leading to the Dark Ages represents a view that can no longer be accepted. During the 4th century the climate seems to have become considerably wetter, so much so that the ladder settlement was under major threat from flooding; a massive dyke to the north of the ladder settlement found through geophysical survey seems to represent a Roman period flood defence.

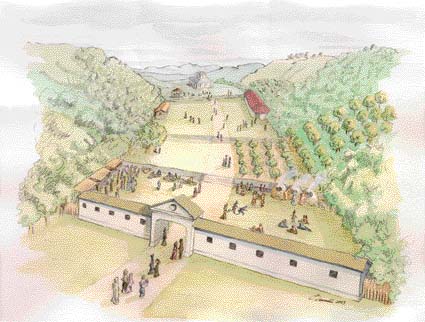

Artists impression of how the shrine complex may have looked at around 350AD Occasional coins recovered from the Roman deposits here indicate that the main building was constructed after AD 340 when a coin was lost during the laying of the foundations, and that it continued be a focus of activity for the rest of the century. The only structure in this complex that can easily be interpreted as a domestic building is a single roundhouse in one of a number of rectangular enclosures around the spring head. It is possible that this could have been the home of a site keeper who guarded and maintained the site between festivals. The exact function of the enclosures established in the late Roman period is not understood. It is possible that they were stock enclosures and that the use of the site in the spring may relate to a fertility cult in which people brought their stock to the site for some religious purpose. Whatever activity was going on, it left more than 30,000 sherds of Roman pottery which, together with the worn pebble surfaces and food debris, indicates that large numbers of people visited the site. Lighting up the Dark Ages: The Early Anglo-Saxon period West Heslerton is unique in that it is the only place in England where a complete Early Anglo-Saxon cemetery and its associated settlement have been excavated and recorded using modern techniques. The examination of these two sites involved excavations covering more than 20 hectares (nearly 50 acres). The Early Anglo-Saxon cemetery, discovered in Cook's Quarry in 1977, started the whole programme of excavation in Heslerton, with large scale field-work on the settlement running from 1987 until the winter of 1995-6. The excavation of the settlement was amongst the largest undertaken in Europe and was made possible by the labours of over a thousand volunteers, mostly working over the summer months. Rarely do we have an opportunity to examine both a cemetery and a settlement together; even more rarely do we have the chance to uncover the full extent of both. The results of this work do however justify the investment. The investigation of the cemetery, which re-used the site of the Neolithic henge and smaller Bronze Age barrows, produced a wealth of new evidence, particularly relating to textiles and clothing. The Prior to the excavation of the settlement in West Heslerton it was thought that Early Anglo-Saxon settlements were small, comprising only a few farmsteads with a limited life span; these would be abandoned when a new farmstead was built nearby. This view is completely at odds with the evidence recovered here; not only does the settlement appear to be laid out on a grand scale with areas for housing, craft and industry, animal husbandry and crop processing, but it also appears to develop during the dying years of the Roman period. The Early Anglo-Saxon settlement in the region has in the past been thought to have begun after AD 450, leaving a Dark Age gap between the end of the Roman period and the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon period. We found no evidence of this empty period; rather, it appears that the Early Anglo-Saxon settlement emerged as the Roman administration was collapsing. Early Anglo-Saxon sites are exceptionally difficult to date precisely; coinage, which provides good dating evidence during the Roman period, goes out of use soon after AD 400 and is not re-introduced until the late seventh century. A dating system based mostly on the brooches and other metalwork found in cemeteries is widely used, but it relies upon relative dates based largely on changing artistic styles rather than absolute dates. Radiocarbon dating techniques have only recently provided sufficiently accurate dates for this period, and we are still awaiting confirmation of some of the Early Anglo-Saxon dates produced using this method. The archaeological evidence can be used to demonstrate that the Anglo-Saxon settlement, which can correctly be called a village, was established directly following the demise of the Roman administration. Had there been a significant gap between the end of Roman activity and the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon settlement phase, we would expect to see a build up of blown sands and other soils separating the Roman from the Anglo-Saxon layers on the site; this was not the case. It appears on present evidence that the village was established at around AD 400, and that it was laid out on a grand scale covering an area nearly 500 metres square. It was established around the spring which had been a focal point of the Roman ritual landscape associated with the shrine and other buildings. Interestingly, the terraced dry valley area which had contained the various shrines linked by pebble paths and surfaces, was not used for settlement and seems to have continued in use as a protected space during the occupation of the village, which ended at about AD 850. Early Anglo-Saxon settlements are quite different to the villages or farmsteads that existed in the ladder settlement during the Roman period. Not only are the architectural styles quite different, but also the mass-produced wheel-made pottery, so common in Roman Britain, disappears and hand made pottery, similar to that in use during the Iron Age becomes the norm. It appears that the collapse of the Roman administration was accompanied by complete economic failure. Early Anglo-Saxon settlements are rarely found built over late Roman domestic settlements and, although the site at West Heslerton takes over a Roman site, it was not a normal domestic settlement. There seems to have been a deliberate break with the Roman world; the creation of new villages away from the established Roman settlements may reflect other factors. We have already seen that the climate changed during the late Roman period; the settlement on the edge of the wetlands was increasingly under threat from flooding and a rising water table. We have often wondered why this settlement was not deserted sooner; it may be that it could not move simply because all the land was owned or controlled by tribal chiefs or the Roman administration. Once this was no longer in place, new settlements could be established in more suitable positions. The Early Anglo-Saxon village was occupied for more than 400 years, during which more than 220 buildings were built on the site. The most distinctive structure type, the `grubenhaus' from the German meaning `hole-in-the-ground house', is of a class not seen in Britain before this period, although commonplace on the continent. These buildings, which seem to have served many purposes, were probably not dwellings. The houses were large rectangular buildings based around an often elaborate series of post settings. Whilst the grubenhäuser are clearly continental in origin, the rectangular buildings seem to combine both native and continental building traditions. The grubenhäuser are very distinctive during excavation, the principal feature being a large rectangular hole in the ground with post-holes to take the timbers that supported the roof at either end. When archaeologists first started to excavate these features, which are invariably filled with rubbish, it was thought that they represented squalid hovels in which people eked out a poor existence in the bottom of a pit covered with a simple roof. Excavation at another similar settlement in West Stow in Suffolk, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, produced evidence that these buildings had raised floors and that the hole provided a dry air space; this cavity floor construction would keep the building above dry and make it last a great deal longer.

If these enigmatic structures did not serve either as homes or weaving sheds then what is their function, and how were they built? One type of structure - the grain store - is alarmingly absent from the settlements of the Early Anglo-Saxon period. If one is to grow crops then it is essential to be able to store sufficient seed for use in the following year; it is increasingly likely that many of these buildings served as grain storage structures, buildings in which a ventilated under-floor space would be almost essential to prevent damp from causing the seed to either rot or germinate. It seems that these buildings performed multiple functions; whilst some were grain stores, others would have been used for general storage purposes. In one part of the village, area 2D, these were the only type of building present. This area seems to have been a craft or processing area, with evidence for metalworking, butchery and a malting kiln found in between and around the structures, which were probably used to store all the associated equipment required to undertake these tasks. The presence of spinning and weaving equipment reflects the importance of textile manufacture, the equipment being stored in these buildings when not in use. No matter how we reconstruct these buildings, they would have been dark inside and therefore useless as weaving sheds; such work most likely was undertaken outside or in the larger timber houses or halls. Evidence from the excavated cemetery 500m to the north of the village shows that a variety of woollen twills and linen cloth were used in Early Anglo-Saxon clothing. One of the most difficult tasks for an archaeologist is the reconstruction of now lost building styles based on the limited evidence found in the ground. At the site of West Stow experimental reconstructions in wood and thatch have been built to help our understanding of how these buildings were constructed. We now believe that rather than being built of wood, grubenhäuser were constructed with turf walls that were pushed into the holes left when the floors were removed. Turf-walled buildings can be remarkably strong, and with the turf growing on the outside face of the walls absorbing any moisture, very dry inside - exactly what is needed for storing seed grain. Fine grey silty soils, found partially filling the under floor holes left when the buildings had gone out of use, seems to be derived from wall material pushed into the hole. In a number of cases concentrations of prehistoric worked flints found in these deposits were probably contained in the turf when it was cut somewhere out in the fields. The roofs were probably made of reed thatch and heather. Until we find a well preserved, burnt down or waterlogged grubenhaus we will remain unsure as to exactly how they were built. Reconstruction of a grubenhaus at West Stow, Suffolk; the figures show dress styles based on evidence recovered from the Heslerton Cemetery The village was large, covering more than 12 hectares, with a population estimated to be ten extended families, or about 75 people. Whilst the grubenhäuser contain a wealth of rubbish which can be used as evidence of daily life, craft, industry and agriculture, the timber halls or houses and their surroundings were apparently kept very clean. These buildings were constructed in a number of styles and sizes, the smaller examples perhaps performing the same functions as the grubenhäuser. They were built of timber with a raised floor, but lacking the dug out air-space beneath. All are rectangular and range in size from 4m to 13.5m long and 3m to 5.5m wide. Although in some areas blown sands had buried and preserved the Anglo-Saxon land surface, we have found no evidence of ground level floors as we might with later medieval houses, which had earth or mortar floors, and we must therefore conclude that these buildings also had raised floors. The timber hall buildings are easily recognised from the rectangular arrangement of post-holes into which the upright timbers forming the main timbers of the walls and supporting the roof were placed. The larger buildings were clearly very elaborate, indicating a high level of carpentry skills; each post-hole contained a pair of cut planks separated by a gap one plank-width wide. It seems most likely that horizontal planks were slotted between the uprights and that these were jointed at the corners where corner posts were absent. The combination of the paired uprights and horizontal planking would have made a strong and rigid platform to support a raised floor in buildings which may well have had an upper half storey. Smaller posts marking a dividing wall, usually found at the western end of the building and defining a space no more than 1.5 metres wide, may have supported a stair-case to the upper level. These buildings, like the reconstructions at West Stow, were probably mostly built of timber; had wattle and daub been used to fill the gaps between the main timbers as occurs in medieval houses, we would have expected to find a lot of it on the site but did not. Plan view of two grubenhauer and associated postholes of timber houses

A grubenhaus before and after excavation

Towards the end of the life of the settlement there is a change in construction techniques, and the larger buildings are constructed with the posts placed in a continuous trench rather than in individual post holes. At this time the number of grubenhäuser reduces and post-built granaries are seen for the first time, based on closely set groups of six or eight large posts. It is possible that the roofs of some of the buildings may have been made using shingles -rectangular split wooden tiles - as we found an iron tool of a type still used to split shingles today. In the centre of the village a spring fed a stream that had been deliberately channelled and which seems to have been dammed to form a pond, the waters of which drove a horizontal-wheeled water mill. It was not possible to excavate this, but a concentration of quernstone fragments and results of a geophysical survey indicate its presence. An Anglo-Saxon mill of this type was excavated in Tamworth during the 1970s; its timbers had been preserved by waterlogged conditions. Beyond the mill the waters drained away following the ancient stream channel which defined one edge of the Anglian cemetery and had been a focus of human activity from the Mesolithic period onwards. A large enclosure to the west of the mill contained debris from threshing, as well as carbonised grain which appears to derive from the late granaries, where some of the grain would have become burnt during the process of drying it prior to storage. The largest concentration of timber houses was found in the north eastern part of the village, laid out without any surrounding property boundaries on a chalk knoll overlooking the valley to the north. All were aligned east-west with either single or double entrances in the centre of the long walls. In the southern half of the site, around the spring, a complex of enclosures, some of which re-use those originally established during the late Roman period, seem to have served to keep stock away from the fresh water emerging from the spring and to provide enclosures in which stock may have been kept over winter. The evidence indicates that most of these enclosures relate to activity occurring during the second half of the period of occupation between AD 650 and AD 850, the Middle Saxon period. In one location, 12AE, a large Early Anglo-Saxon building had been replaced by a Middle Saxon building located on a raised platform that overlooked the whole village and was surrounded by a timber fence on three sides.

About a million animal bones were recovered during the excavation giving us a detailed picture of animal husbandry during this period. They indicate that surplus cattle were commonly slaughtered for their meat at the end of their first or second year, or as their productivity as breeding stock or traction cattle declined. They were probably pastured on the heavy, damp soils of the Vale where vegetation was lush and water plentiful. Surplus young sheep were also culled during the autumnal months, with additional meat sources coming from older breeders that would have been used primarily for wool production. Tooth wear and indications of disease affecting the bones suggests that the sheep were grazed on the coarser pasture of the Wolds. A high frequency of `penning elbow' indicates that sheep were occasionally corralled, whether for breeding, lambing or shearing. Other species such as pigs, domestic fowl and geese offered additional meat sources, although geese and domestic fowl were apparently reared primarily for their eggs. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the analysis of the animal bones has been the discovery that there are too few bones of cattle of `market age'; it seems likely that these were traded and paid as taxation.

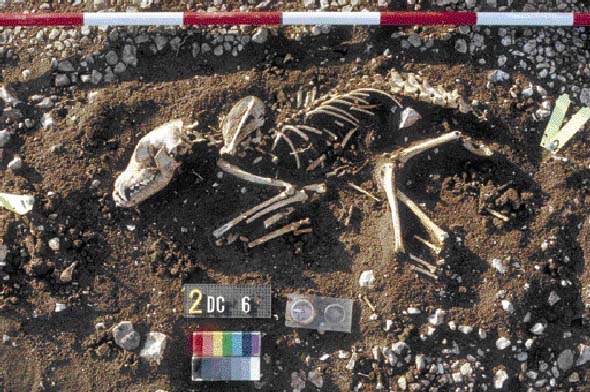

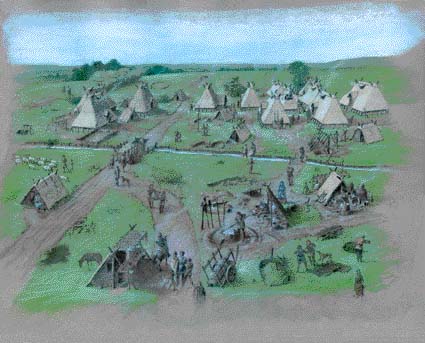

Anglo-Saxon dogs were like deerhounds The village at Heslerton was not a high status site, but one of a number of similar communities around the Vale of Pickering who would probably have paid taxes to the kings of Northumbria. The evidence from the cemetery and the village does not reflect a strong social hierarchy; there is no single building that is much grander than the others and, whilst we assume that there must have been some sort of village leader or chieftain, the evidence is not obvious. The skeletons in the cemetery show relatively good health, with people of similar stature to ourselves, but having a shorter life expectancy, most people not living much beyond middle-age. By AD 850 when the site was deserted, the village would have been a thriving community linked to others in the valley and beyond by trade, travelling artisans bringing specialised goods and skills which could be traded with the community. The end of the village was both deliberate and sudden; the buildings were dismantled, good timbers no doubt being kept to build a new village probably located beneath the present village of West Heslerton. Roofing materials and other debris was evidently burnt leaving a layer of burnt sand, probably blown sand which had been trapped in thatched roofs, filling the latest features. It is most likely that the village was deliberately moved to a more protected location at the onset of the Viking raids. At East Heslerton we have discovered what appears to be a settlement of this date, established behind the later medieval village where it would have been sheltered from view by the wooded slopes of the Wolds, in contrast to the early settlements that were effectively in open country. Artists impression of how the northern part of the Heslerton Anglo-Saxon village may have looked at around AD550 Modern Times: The Medieval and later periods The desertion of the settlement coincides with the beginnings of the English state, in which the role of the individual Anglo-Saxon kingdoms declines until the kings of Wessex dominate the English nation. We have yet to uncover evidence from the Late Saxon period, although carved stonework from this period survives in Sherburn church nearby. It is probably at this time that the new village gets the name Heslerton, the hamlet amongst the hazel trees; we have no idea what name was used to refer to the excavated village. The two settlements of Heslerton Magna (West) and Heslerton Parva (East) emerge during the medieval period, although only Heslerton is mentioned in the Domesday Book. There has been little opportunity to investigate the medieval landscape. A deserted or `crept' village is situated to the south of East Heslerton, and West Heslerton likewise seems to have moved down hill and out beyond the protective slopes of the dry valley in which the church is situated. Geophysical surveys undertaken in the last two years show that the medieval villages of East and West Heslerton had very similar plans including large rectangular enclosures based around the church. The medieval landscape was dominated by rig and furrow field systems in which broad rigs, which in some places are over a metre high, formed strip fields which were shared amongst the population. Very little of these field systems can be seen today; a small area above the crept village at East Heslerton is an important survival. Although most of the rig and furrow has been ploughed flat over the last 100 years, we are able to detect large areas of these fields through geophysical survey and are gradually reconstructing the shape of the medieval landscape.

The deserted medieval villages of East (left) and West Heslerton (right) revealed by geophysical survey Small scale excavations undertaken ahead of development in West Heslerton uncovered parts of a medieval building of probable 14th or 15th century date; this may have been the site of the village brewery known to have existed during the 19th century. The medieval village of West Heslerton was not much smaller than the present village and would have comprised the church, which was sadly heavily `restored' and rebuilt during the 19th century, removing any evidence or early stonework or the wall paintings with which the interior would probably have been covered. Near the church stood the manor house in its own enclosure. This arrangement is easier to see at East Heslerton, where a series of crofts and tofts, rectangular enclosures containing a single property with a garden area, are defined by an enclosing bank and ditch. The houses in the village would have been made either of chalk blocks or of timber with wattle and daub or mud and stud construction on a chalk base, and would have had thatched roofs. During the late 18th or 19th century a brick kiln was established on the estate, and the surviving chalk block buildings were encased in brick, tile and ultimately slate roofs replacing the thatch. Endnote It would not have been possible to draw upon the results of many hectares of excavation and many tens of hectares of survey to describe the evolution of this landscape and its people in this booklet without the continued support of English Heritage. Not only have they supported most of the work, but they have also encouraged us to develop fieldwork, recording and analytical techniques that have earned Heslerton a worldwide reputation. More recently, we have also received support from Cook's Quarry who are funding excavation ahead of sand extraction to ensure that important evidence is not lost altogether. At a time when television programmes show digs, supported by huge resources, that are `completed' in three days, it may be difficult to appreciate the time required to undertake large excavations. During the past 25 years we have spent more than 2000 days in the field; but that's another story!

|

|||||

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s an increase in the scale of sand and gravel extraction for urban regeneration, housing and road building, led to the discovery of hundreds of `new' archaeological sites. These `sites' became clearly visible once the covering blanket of plough-soil had been removed prior to mineral extraction, revealing dark marks in the soil which indicated ancient field ditches, burial-mounds, post-settings for timber buildings and regular outlines of ancient graves. The well-drained sands and gravels often provided a perfect setting for the formation of crop marks showing the layout of buried features, giving archaeologists the opportunity to plan a rescue excavation programme in advance of mineral extraction. At Cook's Quarry a layer of blown sand that lay between the archaeological features and the modern ploughsoil restricted the formation of crop marks, thus hiding evidence of human activity spanning nearly 7000 years. Although a burial accompanied by a jet necklace, dated to about 1800 BC, had been found in the quarry ten years earlier, the discovery had not been followed up. Archaeology was not, however, unknown to the population of West Heslerton. Jim Carter immediately understood the importance of the fragments of metalwork and bone that he found on the quarry surface. He had attended the village primary school and been taught by a remarkable character. Tony Brewster, who later gave up teaching to undertake a series of major archaeological excavations on the Wolds, was a deeply passionate archaeologist who had spent his years as a teacher using archaeology in his lessons at every opportunity. Jim and others in the school had worked on his excavations on Staple Howe, a defended farmstead dating to about 1000 BC and situated just to the west of the village. The site itself had been discovered by two of Jim's contemporaries, Mick Stones and Chick Milner, whilst they were playing in the woods. When, in the autumn of 1978, a small team of us arrived at West Heslerton to undertake a small dig at the quarry, we found ourselves working in perhaps the only village in England where archaeology had been a principal subject at the local primary school throughout the 1950s. We may have had long hair, we may have been students, but everyone understood why we were here and encouraged and supported us from the very first day. We have now benefited from that support and understanding for 25 years.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s an increase in the scale of sand and gravel extraction for urban regeneration, housing and road building, led to the discovery of hundreds of `new' archaeological sites. These `sites' became clearly visible once the covering blanket of plough-soil had been removed prior to mineral extraction, revealing dark marks in the soil which indicated ancient field ditches, burial-mounds, post-settings for timber buildings and regular outlines of ancient graves. The well-drained sands and gravels often provided a perfect setting for the formation of crop marks showing the layout of buried features, giving archaeologists the opportunity to plan a rescue excavation programme in advance of mineral extraction. At Cook's Quarry a layer of blown sand that lay between the archaeological features and the modern ploughsoil restricted the formation of crop marks, thus hiding evidence of human activity spanning nearly 7000 years. Although a burial accompanied by a jet necklace, dated to about 1800 BC, had been found in the quarry ten years earlier, the discovery had not been followed up. Archaeology was not, however, unknown to the population of West Heslerton. Jim Carter immediately understood the importance of the fragments of metalwork and bone that he found on the quarry surface. He had attended the village primary school and been taught by a remarkable character. Tony Brewster, who later gave up teaching to undertake a series of major archaeological excavations on the Wolds, was a deeply passionate archaeologist who had spent his years as a teacher using archaeology in his lessons at every opportunity. Jim and others in the school had worked on his excavations on Staple Howe, a defended farmstead dating to about 1000 BC and situated just to the west of the village. The site itself had been discovered by two of Jim's contemporaries, Mick Stones and Chick Milner, whilst they were playing in the woods. When, in the autumn of 1978, a small team of us arrived at West Heslerton to undertake a small dig at the quarry, we found ourselves working in perhaps the only village in England where archaeology had been a principal subject at the local primary school throughout the 1950s. We may have had long hair, we may have been students, but everyone understood why we were here and encouraged and supported us from the very first day. We have now benefited from that support and understanding for 25 years.

The story of the Heslerton Digs is not just one, but many stories reflecting the hard work, often in bad weather, of more than a thousand `diggers' excavating huge areas over hundreds of weeks of fieldwork. Days of great excitement and discovery more than matched those of despair. Funding has always been difficult to secure, particularly in the first decade when the funds rarely outlasted the digging season. Since then we have been lucky not only to have secured regular funding from English Heritage, but also to have been given the freedom to develop our excavation and recording techniques which have earned Heslerton an international reputation.

The story of the Heslerton Digs is not just one, but many stories reflecting the hard work, often in bad weather, of more than a thousand `diggers' excavating huge areas over hundreds of weeks of fieldwork. Days of great excitement and discovery more than matched those of despair. Funding has always been difficult to secure, particularly in the first decade when the funds rarely outlasted the digging season. Since then we have been lucky not only to have secured regular funding from English Heritage, but also to have been given the freedom to develop our excavation and recording techniques which have earned Heslerton an international reputation.

During the Neolithic or New Stone Age (between about 4000 BC and 2200 BC) settled agriculture is first established and, although hunting and gathering would still have provided an important source of foodstuffs, the growing of crops and domestication of livestock made permanent settlement possible for the first time. During the Neolithic we see the first pottery introduced and the construction of large monuments in the landscape. Eastern Yorkshire is rich in evidence from this period during which the landscape must have supported a considerable population. The direct evidence of settlements is still very sparse, but the burial evidence is both striking and widespread. New technologies were introduced, including polished stone axes which were traded widely throughout Britain, and were efficient tools for both felling and splitting trees. Their distribution in the Vale of Pickering shows that during this period woodland was being cleared aggressively, particularly in the centre of the valley. The construction of large burial mounds, including both long and round barrows, using stone, antler and bone tools, seems to have become widespread indicating that society was organised and that survival was not merely based upon subsistence. There was time and labour to spare from food production to allow for the construction both of complex burial structures and other monuments, in particular avenues of huge posts made from complete tree trunks, and circular monuments surrounded by ditches known as henge monuments. These structures, which derive their name from Stonehenge, are distinguished by a circular enclosure surrounded by a bank and ditch with one to four entrances aligned on the principal points of the compass.

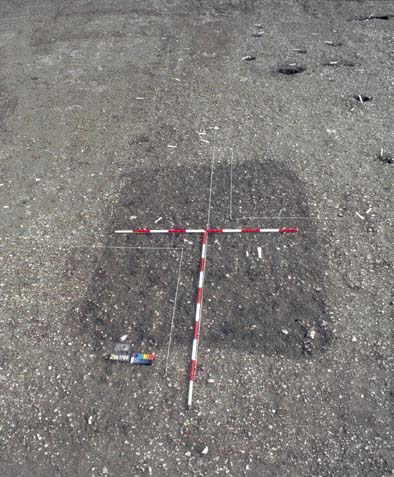

During the Neolithic or New Stone Age (between about 4000 BC and 2200 BC) settled agriculture is first established and, although hunting and gathering would still have provided an important source of foodstuffs, the growing of crops and domestication of livestock made permanent settlement possible for the first time. During the Neolithic we see the first pottery introduced and the construction of large monuments in the landscape. Eastern Yorkshire is rich in evidence from this period during which the landscape must have supported a considerable population. The direct evidence of settlements is still very sparse, but the burial evidence is both striking and widespread. New technologies were introduced, including polished stone axes which were traded widely throughout Britain, and were efficient tools for both felling and splitting trees. Their distribution in the Vale of Pickering shows that during this period woodland was being cleared aggressively, particularly in the centre of the valley. The construction of large burial mounds, including both long and round barrows, using stone, antler and bone tools, seems to have become widespread indicating that society was organised and that survival was not merely based upon subsistence. There was time and labour to spare from food production to allow for the construction both of complex burial structures and other monuments, in particular avenues of huge posts made from complete tree trunks, and circular monuments surrounded by ditches known as henge monuments. These structures, which derive their name from Stonehenge, are distinguished by a circular enclosure surrounded by a bank and ditch with one to four entrances aligned on the principal points of the compass.  radiocarbon date, was the carbonised remains of what appears to have been the blade of a wooden shovel, surviving as fragments of charcoal in the sand. Neolithic shovels, found on other sites in Britain, have generally been made using the shoulder blades of elk or deer; wooden objects so rarely survive we tend to forget that alongside all the stone and bone tools there would have been many others made of organic materials. A large number of massive post pits seem to have provided the settings for possible totem poles, sometimes arranged in regular pairs to form avenues but in other cases dotted seemingly at random around the landscape. During the last three years a number of new examples of these pits have been found as we work ahead of Cook's Quarry, recording the archaeology prior to sand and gravel extraction. The posts in these pits measuring, 50cm-1m in diameter, must have made imposing monuments. In three cases they seem to have provided a focus for cremation burials.

radiocarbon date, was the carbonised remains of what appears to have been the blade of a wooden shovel, surviving as fragments of charcoal in the sand. Neolithic shovels, found on other sites in Britain, have generally been made using the shoulder blades of elk or deer; wooden objects so rarely survive we tend to forget that alongside all the stone and bone tools there would have been many others made of organic materials. A large number of massive post pits seem to have provided the settings for possible totem poles, sometimes arranged in regular pairs to form avenues but in other cases dotted seemingly at random around the landscape. During the last three years a number of new examples of these pits have been found as we work ahead of Cook's Quarry, recording the archaeology prior to sand and gravel extraction. The posts in these pits measuring, 50cm-1m in diameter, must have made imposing monuments. In three cases they seem to have provided a focus for cremation burials.

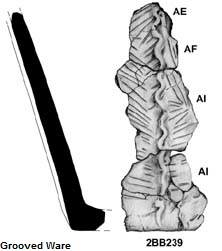

Heslerton, a series of pits containing pottery known as Grooved Ware, and a number of small post-holes may be the first glimpse we have of settlement; sadly the area opened was very small and there is insufficient evidence to identify the type or shape of the buildings supported by the timbers set in the post-holes. Although we do not have stone monuments like the great stone circles found elsewhere in Britain, wooden post circles, circular enclosures, and large and imposing burial mounds seem to have been dotted around the landscape in an organised fashion, concentrated on the sandy slopes overlooking the great wetland and overlooked from the Wolds to the south where truly massive earth monuments such as Duggleby and Willy Howe overlooked another fertile valley, the Great Wold Valley. The broken polished axe fragments and imposing monuments indicate that much of the sandy land between the foot of the Wolds and the wetlands was probably open; the monuments were not only visible to those living and working in the landscape, but each would have been visible from the others. A great post-circle or, more correctly, horse-shoe arrangement of tree trunk sized posts next to the henge in West Heslerton, may have had a role as a kind of observatory or seasonal clock much like Stonehenge; a single tiny post situated at the centre of the arc may have provided a line of sight for identifying the arrival of spring or midsummer using the stars which were, of course, much more visible at a time when there was virtually no light or other type of pollution. For the archaeologist it is often the period of transition between one major period and another that is most exciting to study. The Neolithic was a period of great change; new polished stone tool technology, the widespread use of pottery, the emergence of settled agriculture, and the construction of monumental architecture for both burial and social or political reasons, changed the landscape for ever.

Heslerton, a series of pits containing pottery known as Grooved Ware, and a number of small post-holes may be the first glimpse we have of settlement; sadly the area opened was very small and there is insufficient evidence to identify the type or shape of the buildings supported by the timbers set in the post-holes. Although we do not have stone monuments like the great stone circles found elsewhere in Britain, wooden post circles, circular enclosures, and large and imposing burial mounds seem to have been dotted around the landscape in an organised fashion, concentrated on the sandy slopes overlooking the great wetland and overlooked from the Wolds to the south where truly massive earth monuments such as Duggleby and Willy Howe overlooked another fertile valley, the Great Wold Valley. The broken polished axe fragments and imposing monuments indicate that much of the sandy land between the foot of the Wolds and the wetlands was probably open; the monuments were not only visible to those living and working in the landscape, but each would have been visible from the others. A great post-circle or, more correctly, horse-shoe arrangement of tree trunk sized posts next to the henge in West Heslerton, may have had a role as a kind of observatory or seasonal clock much like Stonehenge; a single tiny post situated at the centre of the arc may have provided a line of sight for identifying the arrival of spring or midsummer using the stars which were, of course, much more visible at a time when there was virtually no light or other type of pollution. For the archaeologist it is often the period of transition between one major period and another that is most exciting to study. The Neolithic was a period of great change; new polished stone tool technology, the widespread use of pottery, the emergence of settled agriculture, and the construction of monumental architecture for both burial and social or political reasons, changed the landscape for ever.

During the Late Bronze to Early Iron Age transition we see the first large-scale land enclosures associated with extensive open settlements and small fortified sites. The increasing use of wheeled vehicles, an increase in population, and the need to manage stock, led to the development of formalised track-ways, their limits defined by hedges and ditches. The skeleton of fields that we see today starts to form and, indeed, some of the landscape boundaries established 3000 years ago survive today as field boundaries and, in the case of West Heslerton, as parish boundaries. By the end of the Iron Age much of Eastern Yorkshire was covered with a great network of enclosures defined by single and multiple banks and ditches; that the banks supported hedges has been demonstrated through the discovery of snail shells from species that live only in a shady hedge habitat. This network of enclosures could have been constructed to define land ownership; however, it is much more likely that they were to assist with stock management and to prevent cattle rustling; wealth was measured in terms of stock not of land. Much of the landscape was relatively open, although the slopes of the Wolds would still have been heavily wooded. The amount of manpower required in establishing this system must have been considerable. The first phase of construction took place at some time between about 1000 and 800 BC when massive pit-alignments were built. These bizarre features comprise pits roughly two metres square, two metres deep, and spaced at metre intervals with an earth bank on either side. We have traced one of these for over 5 kilometres using a combination of excavation and survey, whilst others joining it can be traced using aerial photography running up to and across the Wolds.

During the Late Bronze to Early Iron Age transition we see the first large-scale land enclosures associated with extensive open settlements and small fortified sites. The increasing use of wheeled vehicles, an increase in population, and the need to manage stock, led to the development of formalised track-ways, their limits defined by hedges and ditches. The skeleton of fields that we see today starts to form and, indeed, some of the landscape boundaries established 3000 years ago survive today as field boundaries and, in the case of West Heslerton, as parish boundaries. By the end of the Iron Age much of Eastern Yorkshire was covered with a great network of enclosures defined by single and multiple banks and ditches; that the banks supported hedges has been demonstrated through the discovery of snail shells from species that live only in a shady hedge habitat. This network of enclosures could have been constructed to define land ownership; however, it is much more likely that they were to assist with stock management and to prevent cattle rustling; wealth was measured in terms of stock not of land. Much of the landscape was relatively open, although the slopes of the Wolds would still have been heavily wooded. The amount of manpower required in establishing this system must have been considerable. The first phase of construction took place at some time between about 1000 and 800 BC when massive pit-alignments were built. These bizarre features comprise pits roughly two metres square, two metres deep, and spaced at metre intervals with an earth bank on either side. We have traced one of these for over 5 kilometres using a combination of excavation and survey, whilst others joining it can be traced using aerial photography running up to and across the Wolds.  Tony Brewster excavated two important sites - Staple Howe in Scampston Parish and Devils Hill in West Heslerton. The characteristic pottery associated with these sites is known as Staple Howe ware, and decorated around the rim and body with finger tip or fingernail impressions. Both sites were small hilltop palisaded enclosures, situated on chalk knolls that had in geological time broken loose from the face of the Wolds and slipped down to form small, steep-sided hillocks measuring no more than 85 by 40 metres on the top. The location of these sites, which were surrounded by a massive timber palisade and ditch, provided a commanding view across the valley. Each contained a large grain storage structure and post-holes from possible houses. They may be interpreted as high status properties or, alternatively, as refuges; they were probably both. The discovery of Staple Howe pottery associated with a large number of grain storage buildings and round houses at Cook's Quarry in a completely unenclosed area adjacent to both a trackway and one of the early landscape boundaries, shows that these two fortified or enclosed sites show just one aspect of a well developed landscape.

Tony Brewster excavated two important sites - Staple Howe in Scampston Parish and Devils Hill in West Heslerton. The characteristic pottery associated with these sites is known as Staple Howe ware, and decorated around the rim and body with finger tip or fingernail impressions. Both sites were small hilltop palisaded enclosures, situated on chalk knolls that had in geological time broken loose from the face of the Wolds and slipped down to form small, steep-sided hillocks measuring no more than 85 by 40 metres on the top. The location of these sites, which were surrounded by a massive timber palisade and ditch, provided a commanding view across the valley. Each contained a large grain storage structure and post-holes from possible houses. They may be interpreted as high status properties or, alternatively, as refuges; they were probably both. The discovery of Staple Howe pottery associated with a large number of grain storage buildings and round houses at Cook's Quarry in a completely unenclosed area adjacent to both a trackway and one of the early landscape boundaries, shows that these two fortified or enclosed sites show just one aspect of a well developed landscape.

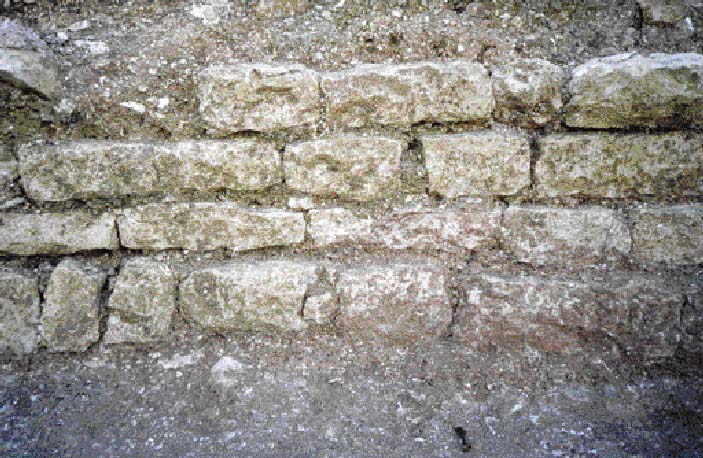

During the excavation of the Early Anglo-Saxon settlement at West Heslerton, our largest excavation, a late Roman stone building was uncovered. This building, which was cut back into the side of a dry valley, the base of which was deliberately terraced by dumping many tons of earth and stone to level each terrace, appears to have been some sort of shrine or small temple. This structure, and fragments of others found on the sides and blocking off the entrance to the dry valley, were associated with large areas of worn surfaces and paths linking the head of the valley to a spring at the bottom. It was not possible to fully excavate the late Roman and earlier deposits on this site, so they have been re-buried and secured for future study. Fragments of other evidence found in later features, and many superimposed