Archaeological Excavations at Roulston Scar

North York Moors National Park

October/November 2013

The Landscape Research Centre

Archaeological Excavations at Roulston Scar, 2013

Prof Dominic Powlesland DUniv, FSA

with contributions from D.James Rackham, Dr. R.G. Scaife and Dana Challinor

Context

The Hambleton Hills situated between the upper reaches of the valley of the River Rye and the Western boundary of the North York Moors National Park are the setting for two hill-forts, one Boltby Scar overlooking the Vale of Mowbray to the North-West and covering an area of little more than a hectare whilst the other, Roulston Scar extending over nearly 25 Hectares with a defensive circuit just over 2Km in length, is by any comparison massive, with a cliff top viewpoint to the south, west and north-west covering a vast area as far as the Pennines to the west and the Vale of York to the south. Small scale archaeological excavations undertaken on behalf of the North York Moors National Park have been carried out between 2009 and 2013 to assess the condition, nature, construction and occupation dates and the potential for recovering environmental evidence from both of these earthen monuments.

Contemporary climate change is changing the invisible below ground environment in ways that may compromise buried organic materials and ancient pollen which perfectly document past vegetation and agrarian landscape histories. Environmental evidence recovered through archaeological excavations backed up by scientific dating reveals a picture of the North York Moors which is quite different from today and contributes to our understanding of the prehistoric and later landscapes and provides a context for the extensive evidence of prehistoric settlement, enclosure and burial that is a feature of the present Moorland landscape. Although the scale of Roulston and Boltby Scar hillforts are very different the two sites have both been severely damaged in the past through 'agricultural improvement' in the case of Boltby and levelling related to the Sutton Bank airfield at Roulston; in both cases large areas of the monuments were bulldozed. Past archaeological activity at both sites has been limited and although it has indicated that both monuments were likely to be Late Bronze Age or Iron Age in date little evidence had been found to help interpret the function and duration of active use of these monuments or give secure chronological framework in which to set these monuments within a broader view of the evolving human landscape.

Archaeological fieldwork on the North York Moors during the last decade in particular including very limited excavation and extensive surface collection campaigns targeted towards the recovery of worked flints have revealed a picture of a prehistoric and later landscape from c.5000BC onwards supporting far larger populations than we might at first think when viewing the current moorland landscape. The distribution of earthen burial mounds or Barrows constructed during the period from c2500BC to 1500BC some of which survive today, even if damaged by antiquarian excavators or perhaps more correctly grave robbers, are evidence of population both in terms of those interred within the monuments but also those who constructed these formerly massive burial mounds. The visibility of these monuments in the present Moorland landscape gives a slightly false impression as those that remain visible features represent a small percentage of these monuments, the rest having been truncated and lost as a consequence of deliberate removal or gradual loss through erosion from agricultural activity. These monuments such as a single upstanding example within the enclosed area of Boltby Scar are frequently found to be the remnants of former monuments that have been heavily disturbed in the past with old trenches backfilled so that an apparently surviving monument is in fact a collection of re-deposited spoil-heaps. The barrows of course were there long before the hill-forts at Boltby and Roulston enclosed them and other than occupying good elevated positions there is no clear relationship between the monuments constructed at times more than 1000 years apart.

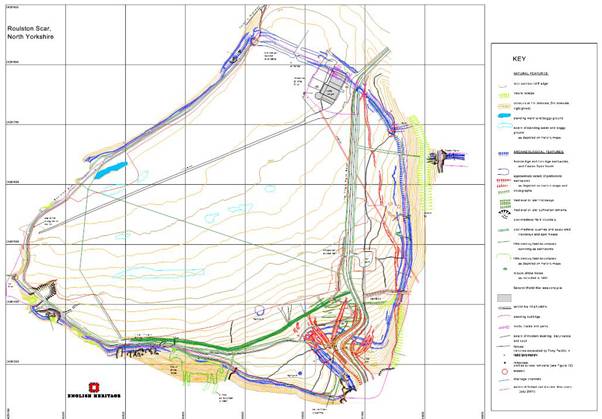

In contrast to the hill-fort at Boltby Scar in which the ramparts enclose a small area of less than a hectare the defences at Roulston Scar measuring more than 2 km in length and containing in excess of 28 Ha, making this one of the largest Hill-forts in the North of England. Like Boltby, but perhaps more dramatically, Roulston is a promontory fort which overlooks the Vale of Mowbray to the north and the Vale of York to the south, occupying a flat plateau with almost vertical cliffs over 300m high on most of three sides, and yet even then with a defensive rampart at the top. The recent history of these two monuments is not dissimilar in that in both cases extensive levelling has taken place within the interior of the monuments, at Boltby, bulldozing undertaken on, in this case a slightly spurious example to achieve 'agricultural improvement'. In the case of Roulston a large part of the interior of this huge monument was levelled by bulldozer during the creation and enhancement of the airfield that has long occupied the hill-fort. Excavations by Pacitto and more recently a detailed topographic survey by English Heritage have enhanced our understanding of this monument identified on the first edition Ordnance Survey maps. Whilst past work had examined the ramparts where they were impacted by the construction of an airfield hangar and mapped in detail the enclosing earthworks in neither case had they demonstrated with any precision the date of the monument or produced the environmental evidence that would allow us to place this monument in its broader landscape and economic setting (Oswald & Pearson 2001, Pacitto 1970,1971).

Figure 1: English Heritage Topographic Survey of Roulston Scar by A Oswald

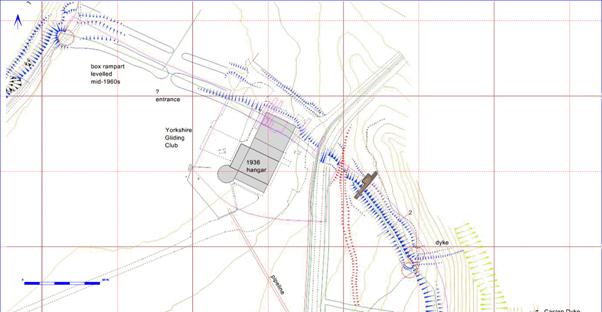

A small excavation project to examine Roulston Scar, with a view to securing dating evidence and assessing the potential for the recovery of good environmental evidence, was proposed during the excavations at Boltby Scar but it was decided that this should not proceed until the excavations at Boltby were completed. A geophysical survey was undertaken covering a 4Ha sample of the monument during 2013 to see if this might expose any details of the archaeology of the interior of the monument; the results although confirming the position of the levelled rampart where it is crossed by the airfield runway also indicated the degree of damage arising from the various levelling campaigns. As at Boltby Scar the underlying geology, calcareous sandstone, and soils were not highly magnetically susceptible limiting the contrast with which features could be seen in the survey results. What was very clear was that in order to gain any insight into the damaged interior of the monument an extensive programme of reasonably large observation trenches would need to be opened, not an entirely practical idea within the confines of an operating air field. Given the extent of the defences a single trench across the defences outside the airfield offered the potential to re-assess the interpretations of the rampart made by Pacitto and English Heritage, to try and secure scientific dating evidence and undertake an assessment of the potential for the recovery of good environmental evidence from beneath the rampart as well as the defensive ditch. The Pacitto excavations and the detailed analysis of the earthworks are discussed in detail in Al Oswald's comprehensive report published by English Heritage (Oswald, A, 2001).

The Excavation

During November and December 2013, a single trench was opened situated 30m to the south of the road bounding the southern edge of the airfield (Figure 3). A site visit in the company of the National Park archaeologist Graham Lee and English Heritage, Inspector of Ancient Monuments, Keith Emerick, earlier in the year had identified a suitable location for examining the upstanding but denuded bank in an areas where the steep scarp slope of the hillside would have amplified the scale of any associated external ditch.

The primary objectives of the excavation were the recovery of:

information to enhance our understanding of the nature and construction of the rampart and any associated ditch as it began to follow the edge of the hill around the monument.

dating evidence both in the form of dateable artifacts or more importantly in material such as charcoal or animal bone suitable for scientific dating.

environmental evidence which could be compared and contrasted with the evidence recovered from Boltby Scar, 4 km to the north.

any material that might hint at the nature and scale of activity at this monument and any relationship it may have had a the Boltby Scar fort.

The location was constrained by the need to avoid clearance of substantial areas of vegetation or tree cover and thus limit any consequential impact on the scrubland covering the site, but was easily accessible by JCB, employed to remove the surface vegetation and thin topsoil.

At the first instance a single 2m wide trench was opened extending from the back of the rampart inside the fort for 21m to the north-east. This exposed the denuded and eroded surface of the rampart and the silty fill in the top of, what was at first considered likely to be a relatively slight ditch, which at this point was cut into the steep slope of the side of the hill.. The rampart sat at the break in slope of the top of the hill and even now whilst seriously denuded is 2 metres higher than the ground on the outer lip of the defensive ditch. When originally constructed an elevation difference between the top of the rampart and the base of the ditch at this point in the circuit could have been as much as 6 metres including any palisade on the top of the bank..

Figure 2: Part of the English Heritage survey showing the location of the rampart where it crossed the neck of the promontory, the trenches excavated by Tony Pacitto beneath the 1971 hanger and the location of the 2014 trench.

Figure 3: Opening the trench

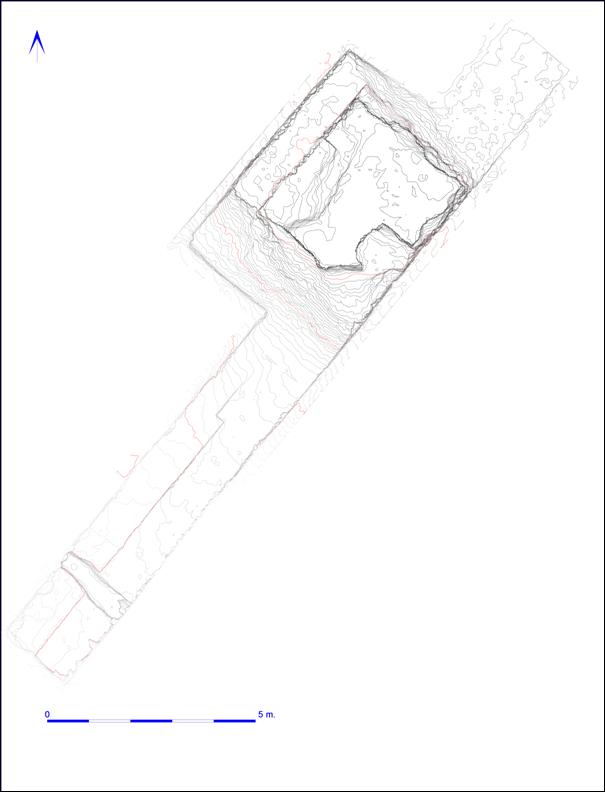

Although a single 2m wide trench cutting through the rampart and ditch had been proposed as the basis for the evaluation it quickly became clear that the scale of the ditch was such that the part of the trench cutting the ditch would have to be extended to ensure the safety of the excavators (see Figure 8). The scale of the ditch matched or was greater than that encountered where Tony Pacitto had excavated 50 to 100m to the North West (see Oswald 2001, pp 17,18, Figs. 10,11).

Figure 4: Ruby Neal and National Park volunteers Catherine Thorn & Judy Bradfield undertaking the primary clean on the outer face of the rampart

Figure 5: removing the upper fills of the defensive ditch

The ditch measuring c.6m wide and 2m deep was cut into bedrock which must have been a massive undertaking, the sides were almost vertical although it was clear that some blocks of bedrock had proven to be too difficult to remove as is demonstrated in the contour survey ( Figure 12 ). The upper fills of the ditch comprised the sort of silty material that has built up over a long period in the top the almost completely filled and stable ditch. The silty upper fills sealed a very stony deposit which may well have been derived from the collapse of stone revetment at the front of the rampart as proposed in 'conjectural phase 2' of Pacitto's excavations ( Figure 7). If the rampart had not employed a stone revetment on the front face then one has to wonder where all the stone removed to create the ditch was put, as the rampart itself is relatively free of large stony layers. There was no indication of any stone rampart facing in the excavated rampart section, however any evidence of such would have been completely removed as a consequence of erosion of the front of the back in this location where the rampart followed the edge of a considerable slope (Figure 4, Figure 5). The ditch did not have any obvious evidence of extensive re-cutting and had evidently filled rapidly with a very rocky primary fill before becoming stable with about up to 1.2m of material in the base of the ditch. A single major cleaning event is indicted in the SE facing section of the ditch, where a silty fill, primarily against the outer face of the ditch filled an ill-defined cut into the primary deposits, this was less visible in the NW facing section and it is likely that as a cleaning or re-cutting event this was more haphazard than the single section might indicate (Figure 13, Figure 14). A charcoal rich burning deposit on the top of the silty fill here was interpreted as the remains of a short-lived hearth or fire within the ditch, this produced an important mid-late Iron Age date, discussed below and indicates that the Hill fort was reworked in the 4th or 3rd century BC (see also online section published using Sketchfab).

The excavations undertaken by Pacitto had revealed that post-holes indicating that a box-rampart construction had been used, perhaps only in a primary phase of the monument as the recorded sections did not indicate the presence of shuttering between the posts designed to retain the rampart. The spacing of the posts at between 2.5-3m was greater than the width of the 2013 excavation trench so we cannot be certain whether the box rampart construction extended as far as the present excavation trench, the position of the rampart here on the hill slope may have deemed the construction of the inherently stronger rampart unnecessary in this position. Most significantly Pacitto examined what he termed a gully at the rear of the rampart, which Oswald interpreted as from a late phase development cutting the back of the rampart, which had contained charcoal from carbonised timbers. The current excavation indicated that this gully or rather palisade slot appears to have continued as far as the present excavation where it was very clear that the slot cut the back of the rampart, the eroded surface of which was buried beneath up-cast from digging the slot. The slot itself contained stone packed post holes indicating that it had contained posts with a diameter of c.50cm. The clear evidence of the buried but eroded rear section of the rampart and the nature of the fill of the palisade slot suggests that the date of this palisade is very unlikely to be prehistoric. A far more likely context is that the defences of Roulston Scar were enhanced with the construction of a timber palisade set into the rear of the prehistoric ramparts as part of temporary fortifications established in association with the battle of Byland on 14 October 1322. In this context Graham Lee has re-examined the complex of earthworks in the hinterland of Roulston Scar and observed anomalies in the positioning of ditches and nature of the two earthworks the Casten Dyke North and Casten Dyke South which may constitute re-worked prehistoric or entirely new earthworks associated. Local historian, John McDonnell summarised that Edward II's forces, pursued by the Scottish army, took up a defensive position somewhere in this area, awaiting reinforcements while King Edward rested at Byland or Rievaulx Abbeys; before escaping south. This force was then routed when the Scots found a way onto the escarpment behind the English forces from the southern flank, focused on an area still known today as Scotch Corner.

The excavation was distinguished by the recovery of a single find, a small eroded fragment of animal bone, probably from a sheep, which was too small and eroded to yield a radio-carbon date and was felt to be poorly stratified in any case.

The excavation of the rampart exposed a very clear turf-line at the base, this included carbonised plant remains which provided a date in the ninth century BC for the construction of the Hill fort, broadly contemporary with the dates for Boltby Scar, Eston Nab and the palisaded enclosures excavated by TCM Brewster at Staple Howe and Devils Hill (Figure 9). The evidence from all these sites indicates that Late Bronze Age to Iron Age transition was a either a period of some turbulence leading to the creation of Hill-forts and smaller palisaded enclosures for defensive purposes or alternatively that they acted as demonstrations of wealth or active power. In the case both of Boltby Scar and Roulston Scar there is no evidence so far pointing to intensive or long term occupation of either of these monuments, although in the case of Roulston excavation within the vast enclosed area has been effectively non-existent. The poor returns from gradiometery need not necessarily indicate a lack of activity but rather a lack of magnetic contrast which limits the returns from this method. The survey and current knowledge do however indicate that the interior of the Hill fort has been extensively bulldozed and re-modelled to improve the airfield that straddles the defences. To the rear of the rampart a more degraded buried soil horiizon survived buried beneath a very stony layer which had a similar soil matrix to that filling the palisade slot perhaps indicating a late date for this deposit (Figure 6).

The excavation was the setting for an

extensive programme of experimental 3D Imaging or 3Di photogrammetry, designed

to supplement the conventional archaeological record with accurate scaled and

textured 3D models which could be published in standard PDF files or

distributed on the web, as 3D models. 3Di offers the archaeologist the

opportunity to generate very high resolution 3D imagery which can be viewed and

measured on a standard computer from any angle in a way not possible using

traditional techniques. The method is particularly well suited to recording

sections and plans quickly and was ideal as a technique for the excavations at

Roulston Scar which took place during difficult cold and wet digging

conditions. The method is used to construct 3D objects identified in multiple

photographs which, with appropriate geo-referencing information used to place

the 3D model in space, can generate 3D computer images with millimetre

accuracy. The 3D models are calculated using Structure From Motion algorithms

which rely upon the use of multiple overlapping images with features that

software can identify across multiple frames so that it can triangulate the 3D

position of each pixel in the images. Once a triangulated 3D surface model is

created then the surface recorded in the photographs is overlain on the model

to create the final 3D image. Careful surveying of multiple reference points

which are visible in the photographs enables the resulting image to be scaled

very accurately. In order to create accurate models a mesh of images is

required so that each point in the finished model is visible from at least

three angles, to create the most accurate and detailed models images should be

gathered close to perpendicular to the trench or section being modelled. To

ensure that good photographic angles could be maintained a 6 metre photo pole

and wireless remote control system were used to generate near vertical images

over the trench. The resulting 3D model built from 170 images has been archived

in Adobe 3D pdf format in the Cambridge University D-Space perpetual digital

archive. The archived 3D model can be viewed at any angle or resolution and

measured in three dimensions on screen. The archived model can be accessed at

(https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/245225) reveals far more detail than could otherwise

be conveniently documented in field drawings and is the recommended point of

reference for this excavation. An annotated version of the same section with

links to the environmental and carbon dating evidence can be viewed using

Google Chrome or Firefox web browsers, which at present provide the best 3D

viewing browser support, at (https://sketchfab.com/models/fe25aae49532418985fc548e5141a3e2).

Figure 6: Geoffrey Snowden cleaning the stony layer immediately behind the rampart

Figure 7: Vertical view showing the dense layer of stone on the rampart side of the filled ditch

Figure 8: final cleaning of the massive flat based stone cut ditch

Figure 9: NW Facing section through the Rampart showing the underlying turf-line and the late palisade trench cut through the rear of the rampart

Figure 10: Isometric view of the 3D Model of the excavated ditch seen from the South East

Figure 11: Ortho image generated from the 3D model showing the excavated trench

in plan

Figure 11: Ortho image generated from the 3D model showing the excavated trench

in plan

Figure 12: Contour plan showing the scale of the ditch (contour interval 5cm - metre contours in red)

Figure 13: 3D rendering of South East Facing ditch section

Figure 14: 3D rendering of North West facing ditch section

Figure 15: Annotated Rampart Section rendered in 3D using Sketchfab as viewed in a web browser

General Conclusions

The excavation of the rampart and ditch section at Roulston Scar was highly successful considering the small scale of the excavation. The most critical question, that of the date of the primary monument, has been resolved and reveals that both Roulston Scar and Boltby Scar are effectively contemporary and part of a much wider group of fortified hilltop sites and most likely associated linear ditch systems that were a feature of the regional landscape and established during the transitional period from the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age; the 9th. and 8th. centuries BC.

Evidence from a burning event in the half filled ditch indicates that the defences may have been revamped during the Middle Iron Age in the 4th or 3rd century BC.

A significant new interpretation of a gully or rather a palisade slot at the rear of the rampart previously thought to have been prehistoric is now far more likely to be associated with re-use of the hillfort in the context of the Battle of Byland in 1322 when Edward II of England was routed by the Scots. No dateable was recovered from this slot, however it appears from the earlier excavations undertaken by Tony Pacitto in 1969/1970 that charcoal was recovered in earlier trenches to the north and it should be a matter of some priority to secure dating material from this feature and properly place this feature in its historical context.

Although the rampart is now much reduced and severely denuded the massive scale and form of the associated ditch shows the vast amount of energy that must have been invested in creating this massive hillfort in the first place. The sheer scale of this monument as a whole with a defensive circuit of 2.1 km is exceptional; the reasons for its construction and how it was used remain un-resolved but these questions could only be addressed by much more extensive works in the interior of the fort. It is possible that the original construction was of largely fiduciary value, created as a demonstration of power rather than as a large fortified population base, it is possible that it served as a major trading centre situated on a tribal boundary and linked to the landscape beyond by drove-way networks and smaller fortified sites like Boltby Scar which may have served as refuges on the droveways.

Compared with Boltby Scar the environmental returns from the excavated trench were very limited, however wetter locations with associated peaty deposits may survive elsewhere and hold a greater potential for the recovery of a more details environmental history.

Aknowledgements

The excavation was undertaken by the Landscape Research Centre on behalf of the North York Moors National Park ; it could not have been undertaken without the generous support of the Yorkshire Gliding Club who not only supported the proposal to excavate but assisted in the provision of plant to open and backfill the trench, and gave free access to their facilities to the excavation team both for sheltering from the worst weather and storing excavation and recording equipment.

The excavation was supervised by Gigi Signorelli assisted by Ruby Neal and was made possible due to the assistance of a number of National Park excavation volunteers Judy Bradfield, Catherine Thorn and Geoffrey Snowdon, despite the poor weather and difficult ground conditions. The excavation could not have been undertaken without the active encouragement and support of National Park Archaeologist Graham Lee and Dr Keith Emerick of English Heritage.

References

Oswald A, 2001, AN IRON AGE PROMONTORY FORT AT ROULSTON SCAR,

NORTH YORKSHIRE, Archaeological Investigation Report Series AI/11/2001, English Heritage,

York

Lee G, 2014 Pers

Comm, insights into the Battle of Byland and the Casten Dykes.

Roulston Scar Environmental Sampling

and Assessment

D.James Rackham

and R.G. Scaife July 2014

Environmental Archaeology

Consultancy , 25 Main Street, South Rauceby, Sleaford,

Lincs NG34 8QG

An evaluation

trench through the ditch and rampart of the hillfort at the Yorkshire

Gliding Club, Roulston Scar was excavated by the Landscape Research Centre. As

part of the evaluation a series of environmental samples were taken from the

exposed deposits to assess the presence and preservation of a variety of

environmental evidence. Three series of samples were taken:

1. A

series of bulk samples (Table 1) were taken from selected deposits for the

recovery of charred plant and charcoal remains, with the additional objective

of obtaining material that could be used for radiocarbon dating.

Two kubiena tins

were taken for possible micromorphological analysis from the

surviving part of the buried soil beneath the rampart.

A pollen series

was taken through the ditch fills (Fig. 3)

The bulk samples

were taken from the lowest silty fill of the hillfort ditch

(context 30 -equating with pollen samples 50-62 in Section 2/3 of Fig. 3); a

charcoal rich deposit just above this layer (context 29) interpreted as

an in situ hearth on the floor of the ditch (samples 1 and 6)

bracketed by pollen samples 66 and 70 on Section 2/3 of Fig. 3; from

the palaeosol beneath the rampart - sample 2 incorporating an element

of the base of the rampart and the underlying soil, and sample 3 the lower part

of the palaeosol with no contamination from the rampart; a soil

(palaeosol) layer immediately behind the rampart; and the fill of a post-pipe

within the later narrow trench behind the rampart (Fig. 1).

Table 1:Site 523AA samples taken for environmental analysis

|

Sample no. |

Context |

Sample vol. in l. |

Sample wt. in kg |

Description/Provisional Interpretation |

|

1 |

29 |

0.8 |

1.057 |

Charcoal rich silt with stones -

? in situ hearth |

|

2 |

|

30.5 |

38.25 |

Base of rampart and top

of palaeosol(transition/interface) |

|

3 |

|

30 |

39 |

Palaeosol below rampart |

|

4 |

|

10 |

10.75 |

Post-pipe fill in later ditch/trench

behind rampart |

|

5a |

|

|

|

Kubiena tin of palaeosl and

base of rampart (see Fig. 00) |

|

5b |

|

|

|

Kubiena tin of base of leached

horizon into lower soil |

|

6 |

29 |

30 |

30 |

Possible in situ hearth |

|

7 |

30 |

28 |

33.5 |

Lower silty fill of ditch |

|

8 |

|

10 |

14 |

Grey soil behind rampart |

|

9 |

Section 2 |

|

|

Pollen series through top half of ditch

section |

|

10 |

Section 2/3 |

|

|

Pollen series through the basal half of

the ditch fills |

Radiocarbon dating

Two samples were

submitted for dating to the Radiocarbon Laboratory of the Scottish Universities

Environmental Research Centre (SUERC). A single indeterminate cereal grain recovered

from the palaeosol beneath the rampart and a piece of

indeterminate roundwood from the charcoal rich deposit [29] with the

ditch sequence.

Table 2: .AMS Radiocarbon dating results.

|

Lab.no. |

context |

material |

13C/12C Ratio |

Conventional Radiocarbon Age |

Calibrated Age at 2 sigma |

|

SUERC-51404 |

Hearth with ditch [29] |

Roundwood charcoal |

-28.3 0/00 |

2263±32 BP |

399-350 cal BC (41%) and 311-209 cal BC

(54.4%) |

|

SUERC-51405 |

Palaeosol beneath rampart |

Charred cereal grain |

-23.10/00 |

2698±32 BP |

905-805 cal BC (94.5%) |

The date on the

cereal grain from the palaeosol would imply a very late Bronze

Age/early Iron Age date for the construction of the hillfort, the grain deriving

from either activity pre-dating the fort or contemporary with its construction.

The date on the

hearth deposit has given a middle Iron Age result indicating that the ditch had

already half infilled by this time.

Bulk samples

The soil samples

were processed in the following manner. Sample volume and weight was

measured prior to processing. The samples were washed in a 'Siraf'

tank (Williams 1973) using a flotation sieve with a 0.5mm mesh and an internal

wet sieve of 1mm mesh for the residue. Both residue and flot were

dried and the residues subsequently re-floated to ensure the efficient recovery

of charred material. The dry volume of the flots was

measured and the volume and weight of the residue recorded.

The residue was

sorted by eye, and environmental and archaeological finds picked out, noted on

the assessment sheet and bagged independently. A magnet was run

through each residue in order to recover magnetised material such

as hammerscale and prill and a count made of the number of

flakes or spheroids of hammerscale collected. The residue

was described and then discarded. The flot of each sample

was studied using x30 magnifications and the presence of environmental finds

(i.e. snails, charcoal, carbonised seeds, bones etc) was noted and their

abundance and species diversity recorded on the assessment

sheet. The flots were then bagged and along with the finds

from the sorted residue, constitute the material archive of the samples.

The

individual components of the samples were then preliminarily identified and the

results are summarised below in Tables 3 and 4.

Results

The samples washed

down to a residue of sub-rounded and fractured sandstone with occasional quartz

pebbles. Sample 6 also included a numbered of heat fractured sandstone pebbles

and a quantity of heated effected sandstone clearly indicating burning and

supporting the interpretation that the charcoal rich layer [30] was an in situ hearth, although it cannot

perhaps be ruled out that this material was thrown into the ditch from a hearth

deposit adjacent to the ditch.

The earliest

sampled deposits derive from the palaeosol beneath the rampart (samples 2 and

3). Very little material was recovered from these samples. A little possible

heat effected stone and small quantities of charcoal with occasional charred

cereal, seeds and nutshell remains. Finds included unidentified cereal grains,

a single glume base of Triticum cf dicoccum, charred seeds of Rumex (dock) and hazel nutshell. A small

number of uncharred seeds were present including bramble (Rubus sp.) and elder (Sambucus

sp.). The sampled palaeosol is well sealed by the rampart deposits (Fig. 3) so

there is some question as to whether these seeds may be contemporary or

intrusive. Bramble and elder are both robust seeds and will survive longer than

most other seeds but their contemporaneity with the deposits cannot be

guaranteed. The presence of a few shells of the blind burrowing snail Cecilioides acicula, a species believed

to have been introduced in the Roman period or later (Evans 1972), is a further

indication of intrusive biological material and might support an interpretation

that the seeds are intrusive. The single unidentified cereal grain from sample

3, the palaeosol deposit, was radiocarbon dated to late Bronze Age/Early Iron

Age (see Table 1).

Three samples were

collected from deposits in the ditch sequence, the grey silts [30] immediately

above the primary loose stone filling, and two samples from the charcoal rich

layer above this [29] which appears to be associated with a hearth feature of

burnt sandstone.

The ditch silting

produced no archaeological finds, but a fragment of possible charred cereal

grain and a hazel nutshell fragment were recovered. A single uncharred seed of

bramble might imply some survival of uncharred material, but as the only find

it is subject to doubt. The charcoal rich layer above produced the largest flot

of charred plant remains and included charred seeds of cleaver (Galium aparine), dock (Rumex sp.), small grass (Poaceae),

eyebrights/bartsia Euphrasia/Odontites),

tubers and a single fragment of chaff. The charcoal assemblage included some

small roundwood and occasional herbaceous stems. The residue included a large

quantity of burnt sandstone (Table 3) indicating a probable in situ hearth. This was the only sample

(6) that produced a magnetic component, probably a result of the burning, but

this included seven flakes of hammerscale, testifying to the presence of iron

smithing nearby on the site at the time, or soon after the hearth was in use.

Figure 16: Rampart section with the two kubiena tins through the buried soil.

Bulk samples 2 and 3 were taken from these layers on the bench opposite the section.

Two samples were

collected from the area behind the rampart. This area had a grey horizon that

appeared to reflect a ground surface that was sealed by slope wash from the

rampart and other deposits, visible as the grey layer on the bench on the trench

floor in Fig. 3. It was thought that this deposit (sample 8) might contain

debris from activities occuring within the hillfort. A little

fire-cracked stone was present, a charred tuber and a fragment of charred hazel

nutshell. The flot was dominated by degraded organic herbaceous stems

and vegetable matter, but apart from a few seeds

of uncharred bramble, elder and nettle (Urtica sp.) no

other identifiable material was recovered. While this evidence gives little

clue to any activities the deposit is also undated. The second sample (4) from

this area was taken from a post-pipe within the narrow trench along the back of

the rampart (Fig. 3). This feature is also undated but may be of much more

recent origin, perhaps associated with the building of new defenses around

the hillfort at the time of the Battle of Byland (AD1332

see Powlesland). Apart from a little fire-cracked stone, a little charcoal and

a charred tuber the sample flot was dominated by degraded herbaceous

stems and vegetable matter much as the other sample from this area. These

degraded organics may have survived from a time in the medieval period, rather

than the earlier history of the site, and might suggest that the material

overlying these deposits has built up over the last few hundred years.

Kubiena tin sampling

The survival of

part of a palaeosol beneath the rampart encouraged the taking of

samples for possible micromorphological analysis. Two overlapping

kubiena tins were knocked into the section to sample the deposits

immediately underlying the rampart make-up (Fig. 1). These bracketed a leached

horizon interpreted as the surviving palaeosol (Fig. 2). The base of

the rampart was composed of slightly gritty sandy clay with a sharp boundary

beneath. Below this was 8cm of pale leached very slightly gritty

and silty sands representing the palaeosol. The subsoil was a

dark yellow brown slightly stoney and iron rich sand

![]()